|

Feature on the bridges of Bosnia

by Slobodna Bosna

As a result of scandalous neglect by the politicians, two world-renowned Bosnian symbols - the bridge on the Žepa, and the bridge over the Drina at Višegrad - might at any moment be wiped from the face of the earth. The Sarajevo weekly Slobodna Bosna, recently published the following report on these cultural and historical monuments about which the Nobel Prize-winning Bosnian author Ivo Andrić wrote some brilliant passages.

The slow death of Andrić’s bridges

Adisa Bašić

‘This bridge, a monument of the sixteenth-century master-builder’s art, endangered by the storage lake on the Drina, was transferred here from the mouth of the Žepa in 1967, so that it may serve further generations’ is carved on a plaque beside a bridge that is hard to reach, and that would doubtless have remained unknown to the majority of Bosnians if the Nobel laureate Ivo Andrić had not written the marvellous story ‘Bridge on the Žepa’ about it.

The beauty and sophistication of the almost five-century-old structure installed in the little Bosnian town of Žepa truly astonishes the traveller who passes that way. For Andrić this bridge was once, among other things, also a symbol of the misfit or disharmony between wild Bosnian nature and world architecture; but today, forgotten, with a grey covering of moss, the bridge looks as if it has grown from the banks of the little river Žepa.

In the house nearest the bridge lives the Kulovac family. Sulejman earned his first wage as a lad helping to rebuild the bridge, when in 1967 it was transferred eight kilometres upstream, to save it from being destroyed by the storage lake for the Bajina Bašta hydro-electric plant. ‘Once the bridge used to attract tourists, and every summer picnics used to be organized there too. Cultural and arts associations from Rogatica, Višegrad and Sarajevo used to visit... and we women from Žepa used to dress up in folk costume, make pies and roast maize, and serve the guests. Today hardly anybody comes to see the bridge’ says Sulejman’s wife Š eća.

Already before the war a big crack had appeared on the bridge, which was then only partially repaired. Not long ago this crack widened and became a clear sign that the bridge - which is supposed soon to be proclaimed a Bosnian national monument - was in great danger. The people of Žepa are attempting to protect their bridge themselves, and have stopped taking heavy loads across it.

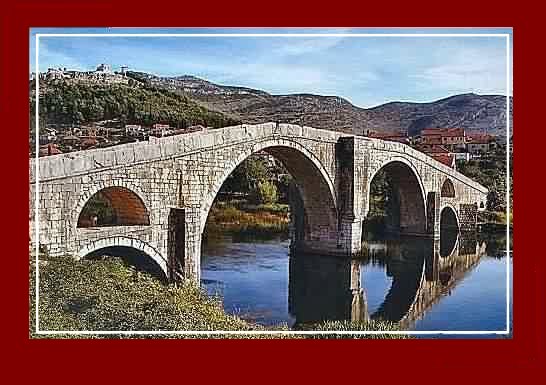

Another, far better known Bosnian bridge that inspired Andrić, the bridge of Mehmedpasha Sokolović, is today equally threatened. A masterpiece of Ottoman architecture, the bridge of twelve arches, 170 metres in length and over 6 metres wide, was built in 1571 by Kodža Mimar Sinan. In the middle of the bridge there is a terrace with stone seats, on which the notable citizens of Višegrad used once to gather, and where there also used to be a fountain for ritual ablutions. In 1886, for aesthetic reasons, a wooden arch and guard hut were removed from the bridge. The bridge at Višegrad survived the great flood of 1896, when the swollen Drina flowed over its walls, but in 1943 the Germans half destroyed the bridge.

Changes in the water level threaten the bridge

Iin the postwar years the bridge was renovated (1949-52) and it was in excellent shape up until the construction of the Višegrad hydro-electric plant. The latter had a legal obligation to protect the bridge, but the conservation and restoration work was interrupted when the war broke out in 1992. For thirteen years already, the stone in the piles of the bridge has been subjected to erosion because of constant changes in the water level: when water is released from the Hydro-electric plant, the piles are largely submerged; but when the level drops, the stone is exposed to the air. The changing level causes rapid weakening of the stone. There remains no trace today of the scaffolding and metal shields erected before the war. A year ago the damage to the bridge at Višegrad became so extensive that the passage of motor vehicles across it was forbidden. However, only rare local inhabitants are really worried today about the fate of the bridge, and some of them even assert that the ban on traffic over the bridge has merely complicated their lives. A group of young people has founded an ecological association called ‘Dreen Team’, which among other things is supposed to work on protecting the bridge; but things have not got beyond the stage of registering the body. The bridge over the Drina, a former tourist attraction, today attracts only a handful of curious visitors. A nearby souvenir kiosk offers Chinese souvenirs and a few amateur oil paintings with images of the bridge. In the town, which has a street, a school and a library bearing Andrić’s name, neither his books nor monographs about the bridge are on sale!

*****

Master builders in Bosnia

Kodža Mimar Sinan (1489-1588), a renowned Ottoman architect whose name is still borne to this day by the most prestigious Turkish architectural faculty, during his fifty-year career built 135 mosques, 57 medresas [seminaries], 22 turbes [mausoleums], 17 imarets [almshouses], 3 hospitals, 48 hans [inns], 35 palaces, 8 haznis [treasuries], 46 hamams [baths] and a great many bridges, of which the best known is the bridge of Mehmed-pasha Sokolović over the Drina at Višegrad. Sinan’s apprentice was Mimar Hajrudin, builder of the Old Bridge at Mostar. Reliable historical evidence does not exist as to who built the bridge on the Žepa. Ivo Andrić before writing his books spent many hours searching archives in Vienna, Istanbul and elsewhere, but even he did not discover the builder’s name. In Andrić’s story, this bridge is ascribed to ‘an Italian master builder, who built a number of bridges around Constantinople for which he won renown’. In his fiction, the unknown builder leaves the village and the bridge without a backward glance, and dies before getting back to Constantinople.

*****

Reflections by Ivo Andrić on the Žepa and Višegrad bridges

Andrić’s Bridges

from ‘Bridges’ (essay): ‘Of all that man erects and builds in his life’s impetus, nothing is better or more precious in my eyes than are bridges. Belonging to everyone and the same for everyone, useful, always erected for a purpose, at a place where the greatest number of human needs intersect, they are more durable than other constructions and serve nothing that is hidden or evil.’

from ‘The Bridge on the Žepa’ (story): ‘The region could not press close to the bridge, nor the bridge to the region. Viewed from the side, its white and audaciously curved arch always used to look isolated and alone, and would surprise the traveller like an unusual thought, gone astray and snared by the Karst wilderness.’

from ‘The Bridge over the Drina’ (novel): ‘Here also in time the houses crowded together and the settlements multiplied at both ends of the bridge. The town owed its existence to the bridge and grew out of it as if from an imperishable root.’

*****

‘The bridges are in great danger of collapsing’

- interview with Amra Hadžimuhamedović, architect and current chairperson of the Commission for the Protection of National Monuments

What is the condition of the bridge on the Žepa, and the one over the Drina at Višegrad?

The bridge at Višegrad is exposed to the highest degree of risk. It could collapse at any moment. I must emphasize, this is a bridge whose architect was Kodža Mimar Sinan, one of the greatest world architects according to UNESCO’s classification. Apart from its historical, documentary, symbolic and ontological value, it is also of incalculable architectural and aesthetic significance. As for the bridge on the Žepa, a n expert team from our Commission is currently carrying an investigation into its condition. The RS government is obliged to proceed in accordance with the ruling issued in 1990 by the B-H ministry for regional planning and environmental protection: i.e. to halt the operation of the Višegrad hydro-electric plant, whose permit for trial operation lapsed on 1 August 1991, because the condition that the piles of the bridge over the Drina must be repaired had not been fulfilled. After that it is necessary to carry out additional specialized structural and laboratory tests on the condition of the materials, and to protect the bridge from further dilapidation. The condition of the bridge on the Žepa will be known to the Commission after the monitoring and the analyses that are in progress, and which should result in the bridge being proclaimed a national monument.

Whose responsibility is it to finance the renovation of the two bridges, and how much will the works cost?

According to Annexe 8 of the Dayton Agreement, responsibility lies with the entity on whose territory a national monument is located. The RS government has this obligation and I expect it to fulfil it. In the case of the bridge at Višegrad there is also a very clear additional obligation on the part of the Višegrad hydro-electric plant, in other words ‘Elektropriveda’, for whose benefit the plant exploits the power of the Drina, thereby imperiling the region’s most important monument. At the beginning of August, the RS minister for regional planning assured me that the condition of both bridges would be brought to the attention of the RS government, and that at the first September session of the latter he would demand the allocation of funds for urgent protection of both bridges from collapse. Implementation of the Peace Agreement, remember, is the responsibility of the OHR, so we expect them to become more involved with this problem. The budgets will be essential elements of the planning documentation that needs to be drafted on the basis of the present condition of the bridges. Each day of postponement means a greater amount of resources that will have to be invested in the repair work.

Has the Commission already drawn up a plan of action for these two concrete cases? What has happened to the plans and works undertaken before the war?

The Commission is not empowered to compile operational documentation. We have identified the measures needed to protect the bridge at Višegrad, and we shall identify them likewise for the bridge on the Žepa. Apart from that, we have initiated the procedure of making the Višegrad bridge a candidate for UNESCO’s ‘world heritage in danger’ list. If the requisite funds are approved by UNESCO, it will be possible to carry out an exhaustive diagnosis. Projects elaborated before the war are useful as documentation, but it is necessary to identify all indispensable technical interventions on the basis of an analysis of the current condition. A decade and a half has significantly altered the condition both of the materials and of the construction.

Is it really possible for the bridges to collapse in the fairly near future from neglect?

It is both possible and likely. In the RS budget for 2004, 500,000 KM have been guaranteed for heritage protection. We expect the major part of these funds to be directed as a matter of urgency to protecting the Višegrad bridge from disappearing, and that measures will also be taken to save the bridge on the Žepa and the ruins of Mehmed-pasha Kukavica’s mosque in Foča.

This interview and the preceding texts have been translated from Slobodna Bosna (Sarajevo), 19 August 2004.

|