|

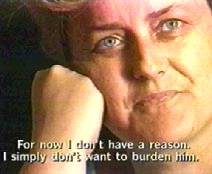

A survivor faces her tormentor

by Sandro Contenta, Prijedor

A few days ago, Nusreta Sivac came face to face with the man who ran the concentration camp where she was raped and others were killed.

It's not uncommon in today's Bosnia for victims and perpetrators of a war that ended in 1995 to cross paths. And nowhere is this more likely than in the Prijedor area, where Muslim victims of ‘ethnic cleansing’ by Bosnian Serbs are returning in force. For Sivac, a pre-war civil court judge who returned in 1999, the chance encounter was especially charged with emotion. Walking towards her was Miroslav Kvocka, a Bosnian Serb she testified against at the war crimes tribunal in The Hague. He was released two months ago, after serving two thirds of a seven-year sentence for war crimes. It's not uncommon in today's Bosnia for victims and perpetrators of a war that ended in 1995 to cross paths. And nowhere is this more likely than in the Prijedor area, where Muslim victims of ‘ethnic cleansing’ by Bosnian Serbs are returning in force. For Sivac, a pre-war civil court judge who returned in 1999, the chance encounter was especially charged with emotion. Walking towards her was Miroslav Kvocka, a Bosnian Serb she testified against at the war crimes tribunal in The Hague. He was released two months ago, after serving two thirds of a seven-year sentence for war crimes.

Human dignity prevails

Sivac screwed up her courage. ‘I hadn't seen him since the trial,’ she says, ‘and suddenly there he was, walking arm-in-arm with his wife, a Bosniak (Muslim) who was my childhood friend. They looked so proud.’ ‘Maybe they thought I would be afraid. But I looked him right in the eyes, and he lowered his head,’ says Sivac, 52. It was a moment of personal triumph for the survivor of Omarska camp, where 3,000 Bosnian Muslims and Bosnian Croats were tortured and starved. On one of Prijedor's bleak streets, human dignity had prevailed.

Sivac's personal moment is part of a larger success story in the Prijedor area, where international pressure and the will of victims to return has gone a long way to reversing the forced evacuation of Muslims during the war. Prijedor's transformation, however, is also the exception. In many parts of Bosnia, wartime ethnic cleansing has become a legally enshrined reality.

Eight years after a gruesome war that turned neighbours into enemies, Bosnia sits in a precarious position. It has made strides to repair the damage, but forces are blocking its progress and stoking its demons. Its stable currency, common passport, and internal freedom of movement are significant achievements. But its economy is near ruin, organized crime and corruption are rampant, and leading suspected war criminals roam free.

And among its three communities - Bosnian Muslims, Croats (Catholic) and Serbs (Orthodox) - talk of reconciliation is drowned out by still powerful fears and hatreds from a war that left 200,000 dead or missing.

Ask a Bosnian Serb about the 1995 massacre of at least 7,700 Muslims in Srebrenica, and he'll respond by talking of a massacre of Serbs at some other place and some other time. Last September, after years of denial, Bosnian Serb authorities finally acknowledged the extent of the Srebrenica slaughter. But they've done little to help international officials find either the mass graves or their wartime leaders, Radovan Karadžić and Gen. Ratko Mladić, who are wanted for genocide.

Insecure peace

Renewed ethnic conflict is kept at bay not by a sense that justice was done, but by war fatigue and the presence of 12,000 NATO troops. The Dayton accords stopped the fighting, but have yet to secure the peace. Adding to the uncertain future is an international community suffering from ‘Bosnia fatigue,’ and sharply reducing its financial backing after pumping more than $6 billion (U.S.) in reconstruction funds into the country.

High Representative Paddy Ashdown, akin to the international community's viceroy in Bosnia, warns: ‘All I would say to my colleagues in the West, gently, is have a look and have a care because the speed at which you are withdrawing international aid from this country could - I don't say will - but could put your investment at risk.’

Ashdown doesn't believe the country will again explode into ethnic conflict. But he doesn't fully rule it out. The greatest danger, he says, is fallout from further economic collapse. He adds: ‘Everybody can go back to war: If we are stupid enough over a long enough period of time - yeah.’

With such troubles, Bosnians ooze nostalgia for their communist past. For 35 years after World War II, Bosnia-Herzegovina was one of six republics enjoying relative peace and prosperity in the federal state of Yugoslavia, headed by Marshal Josip Broz Tito. The fall of the Soviet Union saw Yugoslavia begin to unravel. Tito's successor, Slobodan Milošević, now on trial for war crimes, hastened its demise by unleashing competing nationalisms that engulfed the Balkans in a decade of conflict. In Bosnia, Muslims and Croats voted for independence in 1992, sparking a civil war with Bosnian Serbs. When fighting stopped three years later, mass graves dotted the country and 2.2 million people - more than half the population - were refugees.

The Dayton peace deal divided Bosnia into two entities, each with its regional governments: the Republika Srpska, a boomerang-shaped strip of land hugging the Serbian and Croatian borders, and the Muslim-Croat federation. A third level of government represents all of Bosnia-Herzegovina, but ultimate authority rests with the international community's Office of the High Representative (OHR), whose mandate is to implement the peace accord.

With so much government, opportunities for corruption weren't lacking. ‘We audit different large segments of the economy, and each one reveals mismanagement, misallocation of funds, and out and out corruption,’ says Jason Taylor, senior legal adviser for the OHR, referring to audits of governments and state-owned firms. ‘It has been a tough slog,’ Taylor says.

Lawless space

The international community, which didn't start seriously pushing for reforms until 18 months ago, is partly to blame. By then, the bureaucratic weight of a Soviet-style economy had left 42 per cent of people officially unemployed, and 50 per cent living at or below the poverty line. Bosnia had also developed into what Ashdown calls a ‘lawless space,’ where organized gangs traffic people and drugs. He describes crime as ‘deeply engrained in the cell structure of the body politic.’

Joining the European Union and the NATO military alliance is seen by all sides as their economic and political salvation. But Bosnian Serb authorities are balking at reforms needed to meet a June 2004 deadline triggering the membership process for both organizations. To join NATO, a key criterion is the fusing of Serb and Muslim-Croat armies into a joint command, under the authority of a single minister of defence. ‘There's still not enough trust in this country for the citizens to say "We will have a unified army",’ says Zoran Žuža, chief aide to Dragan Kalinić, leader of the Republika Srpska's ruling Serbian Democratic Party (SDS), which used to have Karadžić as its leader. He says his party has already lost grassroot support from Serbs who believe it has gone too far in giving up regional powers.

‘The alternative to the SDS is radical nationalism,’ says Žuža, whose party campaigned 16 months ago with the slogan, ‘Vote Serbian.’ ‘I don't think these radical forces should be awakened or encouraged. That's why I'm saying the European Union should loosen things up and let us join as we are,’ he says.

Igor Radojičić, a member of the RS parliament and secretary of the opposition Alliance of Independent Social Democrats, sees a chilling future ahead. Older Bosnian Serbs, he says, have the experience of inter-ethnic friendships in pre-war Yugoslavia. But adolescents who lived the ethnic hatreds of the war continue to have that experience stoked in segregated schools, while facing the frustrations of a dead-end economy. ‘This is the generation that will be coming to power in the next 10 or 15 years. It could be frightening,’ Radojičić says.

Says Jakob Finci, head of the Truth and Reconciliation citizens' group: ‘We have a divided education system teaching our children that our neighbours are our enemies. So in 20 or 30 years, we can expect a new war.’ Finci, a prominent member of Sarajevo's Jewish community of 700 people, says the idea of holding a post-apartheid, South African-style truth and reconciliation commission was first proposed by leaders of Bosnia's main religious groups. Draft legislation to set up the commission is before the state parliament. It won't provide amnesties to war criminals who confess. But it will, Finci argues, play a cathartic role for a still traumatized population. ‘Testifying in front of the commission will be part of the healing process,’ he says, insisting Bosnians must recognize the war created victims and criminals on all sides.

Reality of return

Observers looking for a bright spot point to the 1999 property law imposed by the international community, which allows refugees to reclaim their homes. Since then, one million refugees have registered their return, almost half the total displaced. Ashdown calls it ‘a miracle.’ But those who got their homes back didn't all return to live in them.

Kada Hotić and Munira Subaščić are typical examples. Both lost a son and husband in the Srebrenica massacre. Muslims used to make up about 75 per cent of the town's pre-war population, but only about 220 of its 27,000 Muslims have reportedly returned. The apartments Hotić and Subaščić left were immediately occupied by Bosnian Serbs. When they tried to reclaim them under the property law, Republika Srpska authorities dragged out legal proceedings as long as possible. They finally got them back last year, both emptied of all their furniture. Hotić's was also trashed. ‘It's completely ruined. Without big renovations, I can't live in it,’ says Hotić, 58. Adds Subaščić, 55: ‘I could have forgiven them taking all the furniture if only they had left me one photograph of my husband and son.’

To finalize the reclaiming process, both had to register their ‘return’ with local Bosnian Serb authorities. But the women continue to live in Sarajevo. When they visit their Srebrenica flats, they say they encounter verbal harassment and men who took part in the ‘ethnic cleansing.’ ‘One man said, `We raped you, we killed you, we deported you - and still you return. What do we have to do to get rid of you?'’ Subaščić says.

In similar circumstances, many refugees end up selling their homes fast and cheap, often to the person illegally occupying it. Those who do return are often seniors hoping to live out the final years of their lives in familiar surroundings. The younger generation tends to remain in adopted countries abroad. In the Banja Luka area, Catholic bishop Franjo Komarica insists that only 2,000 of an estimated 80,000 Bosnian Croats who left the area returned.

But two examples tell a striking story of success. In 1995, Serb residents of Dvar, who made up 95 per cent of the population, were driven out by Bosnian Croat and Croatian troops. Today, at least 8,000 Serbs have returned and fewer than 800 Bosnian Croats remain.

In the Prijedor region, the entire Muslim population of 49,500 - about 44 per cent of residents - was driven out. In the Muslim town of Kozarac, Bosnian Serb forces in 1992 levelled all the homes residents had left behind. Today, about 22,000 Muslims have returned to the area, many to Kozarac, where international funds have rebuilt the homes. ‘We used to live together before, there's no reason we can't live together again,’ says Husnija Mujkanović, 40, while building his house.

Anel Ališić, 27, was one of the first to return in 1999. He left his refugee family in the United States, got his apartment back in Prijedor, and then joined a non-governmental organization working to facilitate returns. Last December, he organized a seminar that brought together Muslims and Serbs. They toured one of three prison camps Serb forces ran in the area during the war. ‘It's the first time the Serbs went to visit the camps,’ he says. ‘I try to provoke them to think about what happened in the war because otherwise they just don't talk about it. You have young people growing up not even knowing there were camps. Unfortunately, the people are looking at their future without knowing their past.’

This article appeared in The Toronto Star, 23 February 2004

|