|

Popular State: the Radical concept of democracy

by Olga Popovic-Obradovic

At the beginning of the last decade of the last century, in common with all ‘transitional countries’, Serbia under Slobodan Milošević carried out an institutional reform. For all its numerous flaws, there is no denying that the reform created the basic constitutional conditions for the establishment of a modern democratic order: it introduced the principle of the separation of powers, a multi-party system, and direct elections; it set up a parliament and liberalized the media; and, for the first time in Serbia's history, the minister of defence was appointed from the ranks of civilians. A decade and a half on, however, one witnesses the total debacle of these institutions. Instead of paving the way for the establishment of a pluralist democracy, a market economy, and the rule of law, these modern institutions have served as a smokescreen to conceal as well as to help legitimize a totally archaic, anti-modern political project that was also criminal. The matter of state frontiers and ethnic homogenization having been defined as the primary interest of the Serb people, individual freedom as a value either does not figure at all or, at best, is of second-rate importance. One sees a patriarchal-authoritarian and extremely monistic political culture fully at work: inwardly, it manifests collectivism, egalitarianism, and intolerance of otherness; outwardly, it displays ethnic nationalism and belligerence.

‘Democratic’ march to war

As much as it devalued individual freedom and all other values of liberal democracy, the regime of Slobodan Milošević did enjoy a democratic legitimacy - albeit of a populist [völkisch, narodnjački] kind. The Serbs embraced Milošević's policy almost as one, giving it their support as if by plebiscite. So, instead of heading for a free and open society, the Serbs marched to war by their own ‘democratic’ decision, a war which left them the grave legacy of responsibility for war crimes, poverty, and self-isolation.

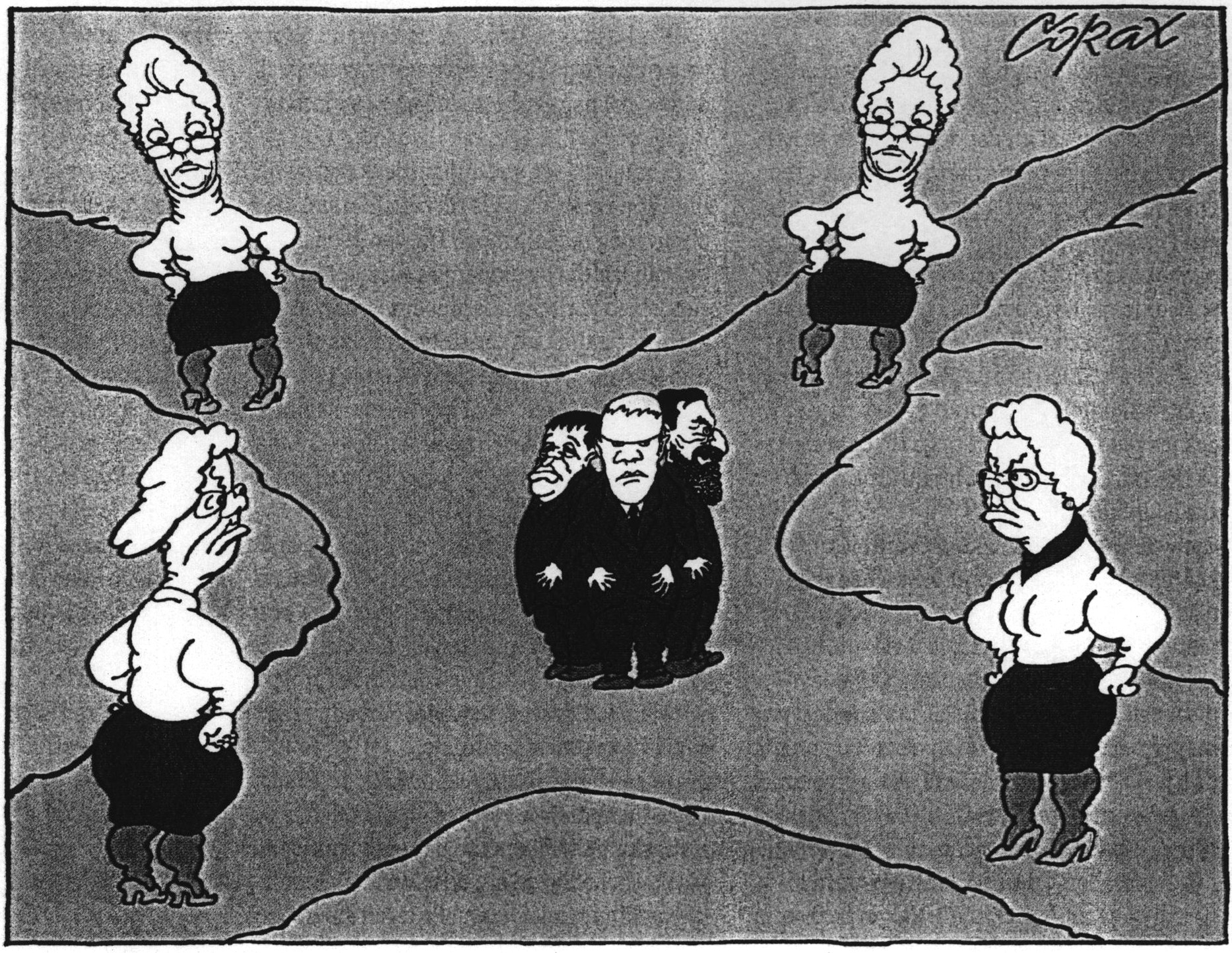

This legacy is very much in evidence in Serbia today. Serbia's electorate, for the most part morally indifferent towards the issue of war and war crimes, continues to put its trust in the promoters of warlike policies - in individuals and political parties with ultra-nationalist and populist leanings - led astray by their nationalist rhetoric, their mawkish archaism and mythomania, and their social demagoguery marked by anti-capitalism and anti-Westernism. The only difference one notices is that this time the emphasis has shifted to social welfare issues, albeit with the programme for integrating all ‘Serb lands’ into a Greater Serbian state still figuring prominently in the political rhetoric. The recent closing pre-election rally in Belgrade of the Radical mayoral candidate, for instance, was a formidable displayof this organic blend of social populism, authoritarianism, and Greater-Serbian nationalism: the candidate's rhetoric, the props, and the disciplined crowd's impassioned cheering and singing in praise of the Radicals' 'father', Hague tribunal detainee Vojislav Š ešelj, were highly evocative of the National Socialist model. The result is devastating.

So over the last 15 years Serbia has voted for the same political option, her expectations merely swinging back and forth between its nationalist and its social populist components. In this, as in all other spheres, 5 October [2000] brought no substantial change.On the contrary, by giving victory to the policy of ‘legalism’ - i.e. continuity with the regime of Slobodan Milošević - the event restored and further reinforced the legitimacy the latter had momentarily lost. For this reason, anyone who professes amazement at this option's current strength is either a hypocrite or politically blind. For one must not lose sight of the fact that the idea of a modern Serbia was dealt the strongest and perhaps the decisive blow after 5 October, subsequent developments furnishing the most dramatic proof that transforming Serbia into a modern state is both a Sisyphean task and a punishable offence. The champions ofa modern Serbia, having previously been branded as renegades and political pests, are now considered fair game. And so it came about that Serbia staged her own ‘murder mystery’: prime minister Zoran Đinđić, who personified the country’s modernizing course and turn towards the West, was stabbed in the back in one way or another by nearly all who matter on Serbia's political stage - generals, journalists, poets, priests. And instead of being called murderers, they were hailed as patriots. The more potential 0Serbia's modernizers possessed, the more ruthless their punishment. Because Đinđić stood head and shoulders above other 20th-century politicians in Serbia, he was got out of the way with unprecedented cruelty. The objective was attained: the prospect of a modern Serbia looks less realistic and more fictitious with each day that passes

***

Roots of anti-modernism

Why has Serbia since the collapse of communism not only failed to recognize the values of modern society as her own vital interest, but stubbornly and systematically opposed them? In other words, wherein lie the roots of the anti-modern political culture that surged to the surface on the wave of ‘democratic transition’ in the late 1980s, only to stay there in order to stifle all diversity?

The usual reply, which blames everything on the communist legacy and nothing else, is quite inane. It even fails to meet the requirements of simple logic, because it does not answer the following two common-sense questions: 1. why was Milošević backed not only by communists but also by anti-communists, including the Serbian Orthodox Church? 2. why is the resistance to modernization visible in post-communist Serbia not to be found in other post-communist countries such as Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Poland, whose brand of communism was more rigid than Serbia's? The stock explanation is especially problematic because it is socially detrimental, blocking as it does any critical evaluation of our own past, hence preventing self-knowledge, responsibility and political maturity. Herein lies the accountability of the elite, for in effect it is instrumental in perpetuating the cultural-political pattern that rules supreme today, by nursing the citizens' distorted and mythologized ideas about the key developments and actors from Serbia's modern history. In brief, the explanation of the debacle of democratic transition in Serbia is to be found in much deeper historical layers: those which precede the communist experience and therefore also account for it.

‘We're not nationalists, we're populists [narodnjaci],’ the Serbian Radical Party vice-president said recently, a reference to the political traditions which brought the party into being and shaped its political agenda. It was these traditions that emerged victorious from one of modern Serbia's crucial and protracted historical conflicts, a conflict between two disparate concepts of society: one generally speaking collectivist, the other individualist.

The content of this conflict was precisely defined by the Serbian political elite at the time of the first serious challenges of modernization, i.e. during the last few decades of the 19th century. The period coincides with the initial political articulation of the broadest strata of Serbian society, made possible by the introduction of a representative system of government and the participation of the people in politics. So the political elite in question derived its legitimacy from the people, from votes of the electorate.

Pašić and the ‘popular state’

The elite's essential characteristic was its deep division over the key strategic issues of Serbian social and state development. The rival projects, whether in open or in latent conflict, were to leave an indelible mark on Serbia's 19th and 20th century history. The conflict revolved round attitudes towards the West as a cultural-civilizational model in the widest sense, giving rise to differences of opinion both on matters of social and economic modernization and on how to conceive the character of the state and its objectives. It was then that the first Serbian Radicals led by Nikola Pašić, in their response to the modernization project of the ruling liberal elite, came up with their ‘popular state [narodna država]’ project on the strength of which they grew into a mass political movement and the biggest political party in the history of Serbia - the Popular Radical Party. The liberal reform-minded elite that ruled Serbia until the early 1890s was not homogeneous either ideologically or in matters of practical policy. For all that, its representatives can be viewed as belonging to the same ideological current, all the more so if one bears in mind the character of the alternative the Radical Party offered. For the nature of this party, and above all its social strength, showed that politics in Serbia are primarily not a choice between conservatism, liberalism, and radicalism in a European sense, but between adopting or rejecting the European civilizational model in the broadest sense, including the character of the state.

The Serbian Radicals' original ‘popular state’ programme rested on a patriarchal-collectivistic and egalitarian conception of liberty and democracy. ‘Our democratism is negative, because it is fundamentally a reaction to Individualism, to Culture. It is a special, intimate kind of collectivism,’ a contemporary critic (Živojin Perić) accurately pointed out. Per se, the programme of the popular state was a negation of the modern state in each and every one of its elements. As the party's indisputable leader Nikola Pašić said, the Serbian state ought to keep the people from ‘adopting the mistakes of Western industrial society, which generates a proletariat and immeasurable wealth, and to raise industry on a co-operative basis instead.....We do not need riches. The Serb tribe is not the tribe of Israel, so money need not flow.’ ‘We are all equals... we are not divided into classes as other nations are,’ said another distinguished Radical, arch- priest Milan Đurić. He could not hide his disappointment that the ‘European court’ (as he called the Congress of Berlin) had instructed Serbia to build a railway ‘instead of rewarding [us] for all those sacrifices with the liberation of Bosnia-Herzegovina and the annexation of Montenegro, thus making us big, powerful and strong in the Balkan Peninsula.’

In order to be able to create and preserve such a state, the entire nation was organized into what was both a movement and a political party, a structure characterized by strict organization, military discipline, and rigid internal hierarchy. Serbia was unique in the modern history of Europe in that, as she took her first steps towards modernization, she also gave birth to a massive populist-socialist political party, organized along lines that others would know only with the appearance of the totalitarian ideologies of the 20th century.

On account of its mass - or more exactly its ‘all-encompassing’ - nature, the Radical Party was ‘popular’ and its power no doubt legitimate; but it regarded itself as possessing sole legitimacy and treated all other political parties as having no legitimacy at all, precisely because they were not ‘popular’. It called the other parties ‘property-owning’, implying that ‘property-owners’ were not of the people and that their participation in government was therefore illegitimate. Being ‘all-encompassing’, the ‘popular’ party regarded itself and the people as one, and its power as popular power. In this way all difference between the popular state, the popular party, and the people as a single homogeneous whole was obliterated, and the principle of no separation between state and society was realized.

Vigilance and the internal enemy

The Radical Party was never to abandon this ‘popular state’ concept, based on its understanding of itself as being one and the same thing as the people. Proceeding from its tenet that it alone was ‘popular’, while all the other parties in Serbia were ‘non-popular’, it used its ‘popular state’ concept to establish a party state behind a parliamentary front, after it had seized power in the May Coup in 1903. Absolute power in the hands of the Radical Party, which identified itself with the people, was what dominated the ‘parliamentary’ experience during the ‘golden age’ of Serbian democracy between 1903 and 1914. The ‘popular’ state never stopped worrying about enemies, so Pašić kept cautioning: ‘The Radical Party must not let its enemies come to power again ... our opponents do not sleep, they scheme day and night, we must keep a vigilant eye on them ... we must be on our guard.’ Because it looked upon the parliamentary system as a war between political parties necessitating constant vigilance, a firm organization, and unquestionable discipline, the Radical Party introduced the idea of the enemy into Serbia's political life.

The party state built on the ‘popular state’ concept, coupled with the idea of the internal enemy, constitute the most enduring legacy of authentic Serb radicalism. Thanks to its deep roots, it has survived all regimes to become a component part of Serbia’s political culture and mind-cast.

Pan-Serb programme

The ‘popular state’ programme had yet another important element: namely, the idea of mission. Although the Radical Party in its formative period paid considerable attention to the question of internal reforms designed to save Serbia from capitalism and bring prosperity to its people, the party leadership left no room for doubt that the country’s foreign-policy programme - which the Radical elite always understood to mean the unification of all Serbs - had absolute priority over internal matters. The leadership's great emphasis on the latter in the early days, however, reflected its faith in the ‘popular state’ programme as a strong mobilizing factor in the planned war for national unification. Arch-priest Đurić, who opposed a class society, made this clear in a parliamentary address: the task of teachers in Serbia has always been to ‘educate children so that they should know the vow ... how as future citizens to avenge Kosovo and create a Greater Serbia ... We must not stand with our arms crossed while the heart of the Serb people is being torn out of our bosom ... Bosnia, the ancient Serb kingdom and Herzegovina, the duchy of St Sava ...’ Pašić was even more explicit, writing the following in his work entitled ‘My Political Confession’: ‘The national freedom of the entire Serb people was for me a bigger and loftier ideal than the civil liberties of Serbs in the Kingdom.’ It was the idea of unifying the Serbs that ‘led me into politics and radicalism’.

Establishing themselves as a party of ‘peasant democracy’, the Radicals succeeded in articulating politically and translating into a genuine popular movement the strong resistance among Serbia's majority peasant population to the process of economic, cultural, and state modernization. Contemporaries noted that on the strength of such attitudes the Radical Party became ‘the people's gospel’, ‘a religious dogma’, ‘a new religion ... in which the people believed fanatically’, just as they ‘believed fanatically in their arch-priests’ (Jovan Žujović). The Radicals capitalized on this non-political, irrational, and almost religious attitude to the party by admitting members on a massive scale and creating an organization characterized by militarist discipline. As far back as the 1890s, the Radical Party organized the masses in Serbia and had them accept its ‘popular state’ idea as their political programme; it also succeeded in achieving the primary and, it seems, decisive political articulation of wider strata of society on the basis of a popular-socialist, and at the same time pan-Serb, greater-state programme.

This article appeared in Helsinška Povelja/Helsinki Charter (Belgrade), no. 57-8, the organ of the Helsinški Odbor za Ljudska Prava u Srbiji/Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia. Address: SCG-11000, Beograd, Zmaj Jovina 7, tel: (+381 11) 3032408, 637116, 637294; fax: 636429, e-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.helsinki.org.yu

|