|

The Srebrenica web

by Aleksandar Hemon

Once, at a Bosnian gathering in Chicago, someone pointed out to me a woman from Srebrenica who had been invited to attend, on her way to Washington. I was told that the woman had lost around hundred members of her family at Srebrenica. I was not introduced to her at that time, but if I had been I do not know what I would have said to her. What can one say on such an occasion? My condolences? Never again?

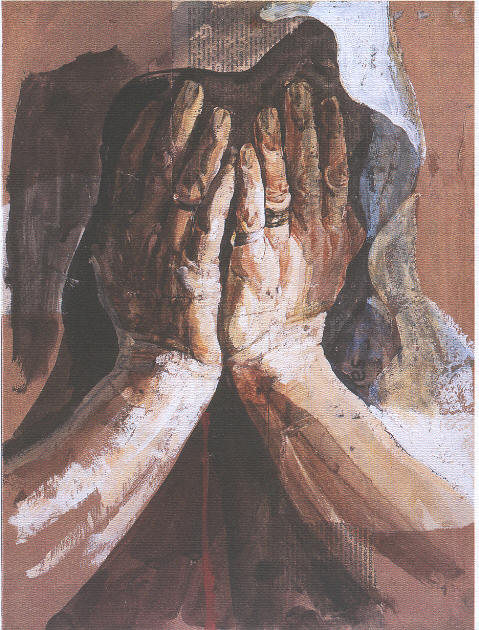

It seems to me that, had I faced her, I could have addressed her only with dead silence, because the dimensions of her loss lie beyond my understanding and thus also my tongue. I would have been ashamed, on the one hand, of the banality of my own ‘problems’ and, on the other, of my helplessness back in July 1995, and later, and always. I am sorry I did not muster the courage to embrace her, but that too would have made me feel fearful and ashamed, because the physicality of my body might have reminded her that, unlike all her own people, I was alive

The dimensions of the crime have had the consequence that every story about Srebrenica is marked with silence, expressed sometimes in the form of phrases repeated so often that they have come to lose their meaning (like, for example: The greatest crime in Europe since World War II. - as if it would be quite another matter if it were the third or the tenth greatest crime in Europe, as if something like this is properly appreciated only because it won the finals of the Crime Cup). There is consequently a danger that Srebrenica will enter the domain of symbolism. It is much easier to imagine what Srebrenica symbolises - the suffering of the Bosniaks; the opportunistic and selfish folly of the EU and the UN; the criminal essence of Republika Srpska; and so on - than what it really is: the loss of a huge quantity of human life, a loss that no one will ever be able to replace.

Every human life is an abundance of unique details, moments and feelings that are totally unrepeatable - no one will ever feel and know what Azmir Alispahić felt and knew, that sixteen-year-old boy from Srebrenica who wanted to become a doctor, and who was killed by the Scorpions before a heroic Serb camera. No one will ever love or be loved like him, and never again will he experience the small and great joys which the living perhaps take for granted (the morning coffee, the scent of lime trees in spring, the scent of your mother’s bosom). And if each human life is a knot in a web of other, emotionally bound, human lives, then Azmir’s web has been torn forever.

Eight thousand times more. This is genocide, this incomprehensible loss of past and future life, individual and collective. This is what the Mladić types had in mind: erasing a huge quantity of life, which could be achieved only by murdering Azmir and eight thousand others. The legal definition of genocide is easily understood (except in the Wooded Republic and the bearded regions of Serbia and Montenegro), but the human consequences of genocide are incomprehensible: all that life was, is and could be disappears; whole worlds are devastated. The woman who lost a hundred members of her family is a knot bereft of its web.

All other citizens of Bosnia-Herzegovina, and in the last instance the whole of humanity, are part of that web, however, so our lives too became irrevocably changed with the disappearance of those eight thousand boys, young men and old men. We live in a world that would have been different if Azmir had not been killed: maybe by now he would have completed his medical studies, maybe he would be saving someone’s life in the Srebrenica hospital, maybe he would have told me a story worthy of being retold and written down. Despite all the symbolic Srebrenica operations and commemorations, speeches and phrases, it is my belief that all those whose life is bound up - regardless of where they live, and however minimally - with this unhappy country, all those whose mind is open to the idea of a world in which all fates are ineluctably linked, they all feel, because of Srebrenica, a greater or lesser void in their souls and around them. We miss Azmir all the time.

Every time I come to Sarajevo and Bosnia I experience a permanent dislocation in the structure of reality, I notice that - as Hamlet said - the time is out of joint. The symptoms are there at every step: the ruins in the middle of the city stinking of shit and urine that no one notices any longer; the placards in the GSP trams saying that bringing corpses on board is strictly prohibited; the grandmothers begging on streets that few people use, perhaps because they are ashamed; the Chetnik Paravac inspecting a de-mining unit of the Bosnian-Herzegovinian army, which he approves only in order to send it to Iraq; the natural and unselfconscious manner in which conversations about football turn to war crimes, and vice versa. The greatest dislocation by far is the existence of this Dayton Bosnia, a state in which members of the parliament and presidency belong to parties that do not recognise it; in which the ideological followers of war criminals rule over their victims - all in the name of a co-existence that concerns them as little as Azmir did. This dislocation in reality grinds and oppresses; it leads to experiencing the world as a desert devoid of human feeling, a world in which Azmir would again be killed with equal brutality. We have done nothing to save Azmir this time.

In Srebrenica, then, the world is out of joint, and it is our duty to try to return it to its place, so that our children’s children might at least live normally, whatever that means, so that some future Azmir will have a chance to survive. In order for this to be possible, it is necessary to preserve Srebrenica in all its concreteness. It is necessary to bury the victims decently and to condemn the criminals; to learn their names; to know what happened, when and why. It is necessary to be able to imagine the past and future lives of Azmir and of all who were killed in Srebrenica; to listen to those for whom Srebrenica is more real than their own life. If I were to meet again the woman from Srebrenica whom I did not dare address in Chicago, I would still not know what to say to her, but I would know that I should listen to her, because she knows all that one can know about Srebrenica - because we must weave a new web from her knot.

Translated from Dani (Sarajevo), 1 July 2005

|