|

Pompous ceremonies will do nothing without justice

by Jonathan Steele

The river Drina, which snakes along Bosnia's eastern border with Serbia, was at its most lovely. Dragonflies darted across the diamond-twinkling shallows near the bank. Shafts of sunlight touched the edges of the otherwise impenetrable woods on the far shore. Then we heard the firing. Spaced-out single shots at first, followed by automatic fire. Hunters on the prowl, it seemed, letting off when they spotted prey. We peered through binoculars, but the trees were too tight to reveal any movement in their shadows. Our sight was blocked, but it seemed certain we had become ‘ear-witnesses’ to the final murders in Europe's biggest massacre since the second world war. The river Drina, which snakes along Bosnia's eastern border with Serbia, was at its most lovely. Dragonflies darted across the diamond-twinkling shallows near the bank. Shafts of sunlight touched the edges of the otherwise impenetrable woods on the far shore. Then we heard the firing. Spaced-out single shots at first, followed by automatic fire. Hunters on the prowl, it seemed, letting off when they spotted prey. We peered through binoculars, but the trees were too tight to reveal any movement in their shadows. Our sight was blocked, but it seemed certain we had become ‘ear-witnesses’ to the final murders in Europe's biggest massacre since the second world war.

Srebrenica, where 25,000 Bosnian Muslims thought they were under international protection, had fallen to Bosnian Serb forces six days earlier. Thousands of men and boys had been killed in warehouses and abandoned factories to which they fled when the town's defences crumbled. Hundreds of others whom the Serbs deceitfully permitted to walk towards Muslim-held territory were ambushed and slaughtered. What we were hearing were the deaths of the last escapees, who had run into the woods hoping to trek to the Drina and swim across. These grisly forest manhunts, which any local Serb was invited to join, were not new. Serbian commanders dubbed them ‘cleansing the terrain’, a kind of ethnic cleansing in miniature, once the paramilitaries' main work of evacuating a Muslim town or village was over.

Access to the Srebrenica area from anywhere else in Bosnia was blocked by checkpoints. Crossing the Drina from Serbia might be possible, we speculated, or we might find people coming out who had seen something. At Ljubovija, a village close to the UN base at Potocari, where most Muslims had fled when Srebrenica fell, we saw vehicles from the International Committee of the Red Cross preparing to cross the bridge. After blocking humanitarian access for a week, the Bosnian Serb commander, General Ratko Mladic, was permitting medics to retrieve around 50 wounded Muslims. It was a cynical effort to deny tales leaking out that every Muslim male was dead. The bridge guards said no journalists could pass. An effort to interview a young couple who had just driven from Bosnia was equally fruitless. Angry neighbours ordered them to say nothing, and amid rising tension we were told to leave immediately ‘for your own safety’.

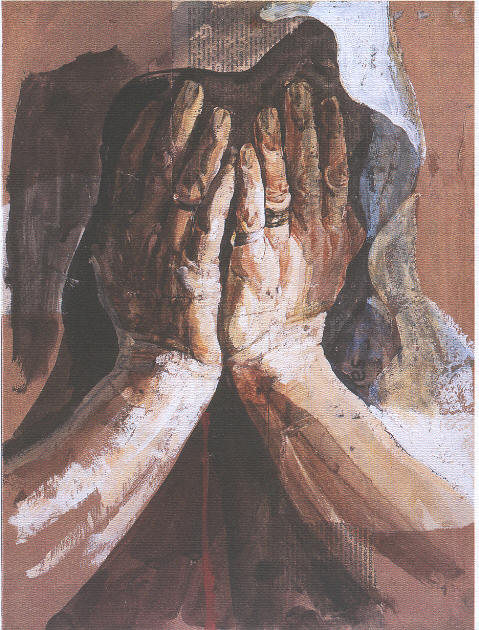

Back in Belgrade, it was hard to believe we were only two hours' drive from horror. On the cover of his brilliant study States of Denial: knowing about atrocities and suffering, Stanley Cohen depicts a person with hands clamped over both eyes. But what does a society most of whose members are in denial look like? To judge from the Serbian capital 10 summers ago, the answer is ‘nothing special’. The pavement cafes off Belgrade's Republic Square were packed as always. Elderly matrons filled the wickerwork armchairs of the Russian Tsar, a haunt of the upper middle class. Media types sat outside a glass-fronted bookshop 20 yards away. Students flopped and flirted round the corner near the bus stops.

The Women in Black, an extraordinarily brave group who silently held anti-war placards in the square every Wednesday for an hour, now added a new one with the word ‘Srebrenica’. As usual, a few passers-by shouted or sneered. Everyone else ignored them. Ten years later, their protests continue. The main architect of the Balkan wars, Slobodan Milosevic, is in The Hague, but Serbia is largely still in a state of denial about the crimes committed in its name - and the same applies to Croatia. Any hope that the Milosevic trial and the evidence painfully being laid out in public would have an educative effect was dashed long ago.

One small Srebrenica episode, the execution of six Muslim prisoners by the Scorpions paramilitary unit, was recorded on video. Another of Serbia's bravest women, Natasha Kandic, who runs the Humanitarian Law Centre in Belgrade, obtained it recently from a Scorpion who was not one of the killers. She persuaded the cassette's owner to let her reveal it after he vanished abroad. She gave it to The Hague tribunal and it was shown on Serbian TV. For a day or two the video was a media sensation, not least because it showed the executioners laughing and jeering at their victims. Those paramilitaries whose faces were visible were arrested, but a resolution to get the Serbian parliament to condemn the massacre at Srebrenica fizzled out. The party of Vojislav Kostunica, the prime minister, as well as the ultra-nationalist Radical party and the remnants of Milosevic's party, reduced it to an anodyne condemnation of all sides in the Balkan wars. The resolution's supporters angrily withdrew it.

In 10 days there will be a pompous commemoration at Srebrenica to which Jack Straw and other dignitaries will go - though not Boris Tadic, Serbia's president. The widows of Srebrenica have told him not to bother now that the Serbian parliament has refused to condemn the massacre.

In a haunting documentary that BBC2 will show on the anniversary, Leslie Woodhead portrays the depressing town as it is today, with a Muslim mayor elected in an internationally organised poll who dares not actually live there. One of four survivors on whom the film focuses talks with mixed feelings of the anniversary ‘spectacular’. Western politicians jumping on the bandwagon have the benefit of pumping up international memories for a few days, he admits, but private memories can never be healed without justice. Of this there is little sign.

During the decade in Bosnia since the war ended, thousands of NATO peacekeepers have made only three attempts to arrest Radovan Karadzic, the Bosnian Serbs' former leader. Mladic lives in Serbia while the EU does nothing more to get him arrested than issue vague promises of opening the road to membership if the Serbian government persuades him to go to The Hague.

Several indicted criminals from other Balkan countries have surrendered, and the past few months have seen a slight acceleration in the flow of senior Serbs. But until Mladic, the worst murderer, is behind bars, the stain of Srebrenica will tarnish western governments as well as Serbia.

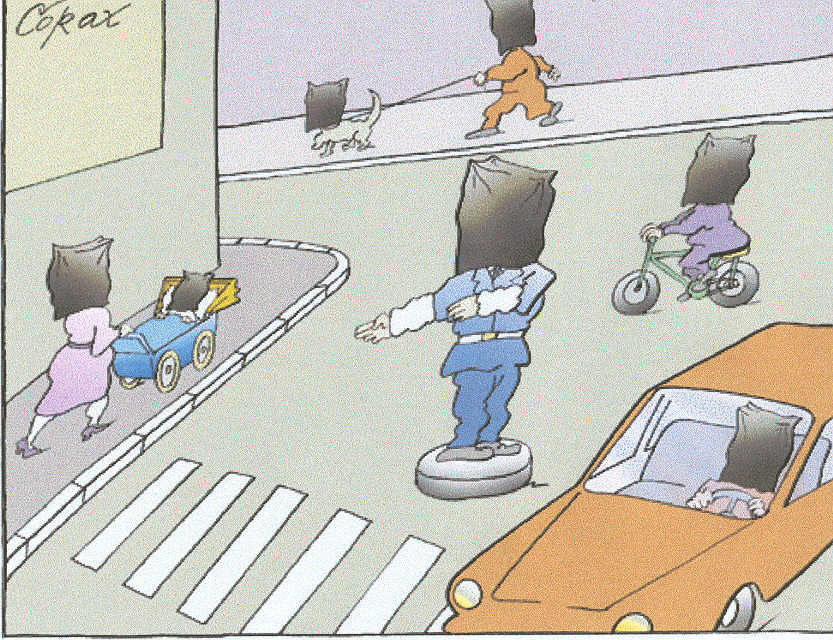

As the Women in Black put it, the Serbian parliament's refusal to condemn the massacre shows Kostunica is continuing where Milosevic left off. ‘From the politics of state-organised crime, they have moved to institutional denial,’ the group says in an anniversary statement. If the authorities admit a crime, it is only to justify, minimise or relativise it. Cultural patterns, value systems and the ideology of nationalism show, in its view, that the climate that produced the war remains. And the parade of snappy dressers in Belgrade's smartest street cafes is still a guilt-free zone.

This article appeared in The Guardian (London), 1 July 2005

Corax, Vreme (Belgrade)

|