|

Murder of a Serbian premier

by Gordan Malic

Miloš Vasić ‘s book The Assassination of Zoran, in which he examines the rise and activities of the criminal Legija’s cartel and supplies new details about Đinđić’s assassination, was published on the second anniversary of Đinđić’s murder. Its fifty thousand copies were sold out within two days. Miloš Vasić ‘s book The Assassination of Zoran, in which he examines the rise and activities of the criminal Legija’s cartel and supplies new details about Đinđić’s assassination, was published on the second anniversary of Đinđić’s murder. Its fifty thousand copies were sold out within two days.

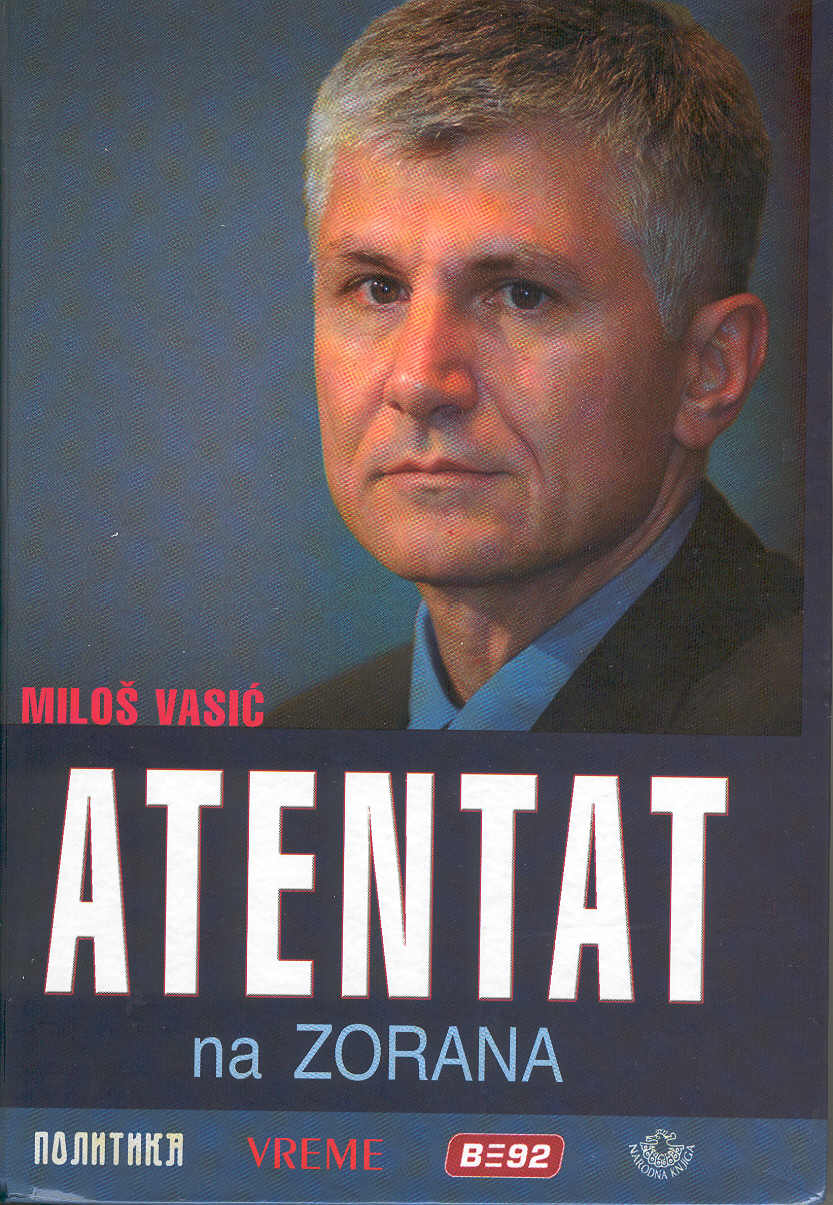

Miloš Vasić, Atentat na Zorana [The Assassination of Zoran] , Politika/B92/Vreme/Narodna Knjiga, Belgrade 2005, 303 pp.

Legija’s criminal cartel

Is life in Serbia better today than before 12 March 2003, the day that Zoran Đinđić was murdered? This is the question which Belgrade journalist Miloš Vasić poses at the end of his book. The work gives a negative answer. 50,000 copies were sold within two days: as the author argues, the late Serbian prime minister is more popular today than on the eve of his death. Those who read Vasić’s book will not get the answer, however, to the most important question of who ordered his assassination. According to Vasić, it is possible that the names of those who ordered or inspired the crime will not be known even after the end of the trial against those indicted for it (Miodrag Luković ‘Legija’ and other members of the Red Berets). The list he provides of those with an interest in Đinđić’s death is quite extensive, and based on solid research. Đinđić’s murder was the work of a criminal cartel which has survived Slobodan Milošević. At the same time, argues Vasić, it was the product of political provincialism, hesitation and opportunism on the part of the government produced by 5 October [2000].

He takes the term ‘cartel’ from the works of the eminent Serbian political scientist Nenad Dimitrijević, who uses it to describe the state of prolonged absence of the rule of law in Serbia. Đinđić was killed, in other words, by Milošević’s Serbia, which had rid itself of its increasingly isolated dictator some time earlier. It responded to Milošević’s defeat by surrendering him to The Hague, and to Đinđić’s reforms by killing him.

Birth of the cartel

Vasić places the true date of the cartel’s birth in August 1991, when Milošević, having lost his last hope in a counter-revolution in Russia, decided in the absence of significant help from Moscow to mobilize his own forces for a war against the rest of Yugoslavia. After the Pan-Slav and Yugo-Communist options had failed him, he opted for the Serbo-Chetnik one. ‘The mobilisation crisis [i.e. the poor response to the call-up] helped him in this, since it opened the door to volunteers, war profiteers, common criminals and looters, as well as to political fanatics. The prisons were empted of "volunteers"; those selected by the late Arkan at Zabelas and Mitrovica were included in his Serb Volunteer Guard.’

The Red Berets were already engaged on the ground, concerned with the training and organising of Serbs - and ‘doing business’ on behalf of the Serbian state security service: recruiting policemen, keeping under control various semi-wild elements in ‘all the Serb lands’, and acting as the iron fist of Milošević’s regime by way of special operations, infiltration and subversion - outside Serbia. The Berets were given special tasks also within Serbia.

Their services were paid in all kinds of ways, from permission to loot (which the Serb Volunteer Guard turned into an industry) to black marketeering in fuel, cigarettes and strategic goods, and to privileges in currency trading and other financial dealings at the time of the hyperinflation. Patronage over the majority of these activities was provided by Mihalj Kertes, the Godfather and head of Customs, who together with state security chief Jovica Stanišić ensured that goods crossed the borders unhindered. And, of course, heroin was the most profitable commodity of all.

‘The exodus from Croatia would later fill the special operations unit with cadres like Gumara, Š kendeta, Priko, Leo, Žmigij and so on. Transfer from the Serb Volunteer Guard brought to the special unit (JOS) Milorad Ulemek Luković Legija and dozens of other characters like him’, writes Vasić.

Revenge and murder

The cartel literally pulverised its street competitors, while having no political master other than Slobodan Milošević. Vasić argues that killings were arranged in private encounters between Milošević and Legija. This is how the murder of Slavko Ćuruvija, the newspaper publisher and owner of Dnevni Telegraf, was arranged, while the killing of SPO leader Vuk Drašković was discussed on several occasions, beginning with October 1990. During 2000 the ‘pond’ shrank: Željko Ražnatović Arkan was killed, Pavle Bulatović the FRY minister of defence was also liquidated. And then on 25 August 2000 Ivan Stambolić, Milošević’s former best man and later political opponent, was kidnapped and shot.

Vasić believes that Đinđić was unaware of the nature of the cartel, though he feared it. In his childhood he had mingled with ‘dare-devils’, knew how to win their friendship, and enjoyed their company though he did not share their preferences. Hence Đinđić’s acquaintance with Ljubiša Buha nicknamed Čume, the head of the Surčin mafia clan, who subsequently became a state witness against the competing Zemun gang. Đinđić’s conviction that friendship with these criminals could pay off also at the political level proved fatal. Although he did not need the kind of services required by Milošević, Đinđić was at one time convinced that he could not bring down Milošević without the help of the Red Berets. Vasić argues that this was a tragic misjudgment. Legija courted Đinđić and DOS, telling them that he would protect them and they should not fear him. On 5 October 2000 a million people took to the streets of Belgrade, a number sufficient to start and end a revolution, he writes. At that moment Legija had only seventy people, many of whom were not in the city but scattered across Serbia.

Legija was unable to stop the demonstrators, who were joined by sections of the army and the police. He tricked Đinđić by walking up to him and telling him that ‘today the people has won’. He sided with DOS before Đinđić became fully aware of what this meant, writes Vasić. During those days the DOS leaders were besieged by criminals and members of a variety of special units wishing to ‘protect’ them from ‘Milošević’s killers’. Legija was among the first to arrive, and because of his relationship with Milošević he was the most important of them. When it was needed, his unit also staged a cheap display of force in front of Milošević’s home; but, as Vasić writes, the meeting between Milošević and Legija on that occasion went off like a meeting between father and son. Legija’s unit survived the democratic change, together with much of the cartel. Not until just before his death did Đinđić consider it politically opportune to settle accounts with the criminal inheritance of the Milošević regime. In the meantime the nationalist Vojislav Koštunica and his DSS became the new political shelter for the members of the cartel.

Feeble responses

In late 2001 and early 2002 the cartel’s activities came to include kidnapping people and releasing them for huge ransoms. Legija’s clan soon came into conflict with that of Buha Čume from Surčin, and Legija tried twice to murder Čumet, first by poison and then by bullet. At this time DOS had formed the government and faced the consequences of ten years of Milošević’s chaos. New men took over the ministries of the interior and state security (Dušan Mihajlović, Zoran Mijatović and Zoran Petrović), but a significant part of the cartel remained untouched. Milorad Bracanović, a cadre close to Legija, survived all personnel changes and advanced to become the head of the Belgrade BIA, a new name for the old state security service.

Legija’s informers briefed him on the investigation of the Berets, i.e. of their role in the failed assassination of Vuk Drašković, the murder of Ivan Stambolić, mafia killings, kidnappings, etc. Đinđić’s opponents warned Legija that he could be delivered to The Hague. What followed was the Red Berets’ rebellion, which Đinđić again failed to take seriously.

According to Vasić, the prime minister’s responses were always late and inexcusably feeble. Worst was his reaction to the attempt on his own life on the motorway. As has been established at the trial of Legija and others, the assassination plan had several variants, from using a lorry to cut in front of Đinđić’s motorcade to firing grenades at his car. When the first variant failed, Đinđić’s bodyguards pulled a certain Bagzi Milenković, a member of the Red Berets, from the truck and - quite unprofessionally - passed him on to the police for causing a ‘traffic accident’. Đinđić habitually showed little desire to deal with crime, because it nauseated him and because he had no time for it, writes Vasić.

IN BOX

According to Vasić, 5 October was not a simple change of government but a revolution, Such events demand statesmen who can make brave and wise decisions, not politicians with the mentality of a provincial lawyer, like Vojislav Koštunica. Following Đinđić’s death, the cartel busied itself with besmirching his image among the population. Articles appeared about his ‘mafia links’, his ‘murky business deals’ involving cigarettes and drugs. Part of the controlled media carried stories about Đinđić that would be repeated by Legija, who had organised the murder. The cartel tried in this way to put an end to the anti-mafia investigations that had begun after Đinđić’s death. Vasić includes under this heading the pressure to replace prosecutors Jovan Prijić and Marko Kraljević, which he says came from Koštunica himself.

Translated from Globus, Zagreb, 18 March 2005.

|