|

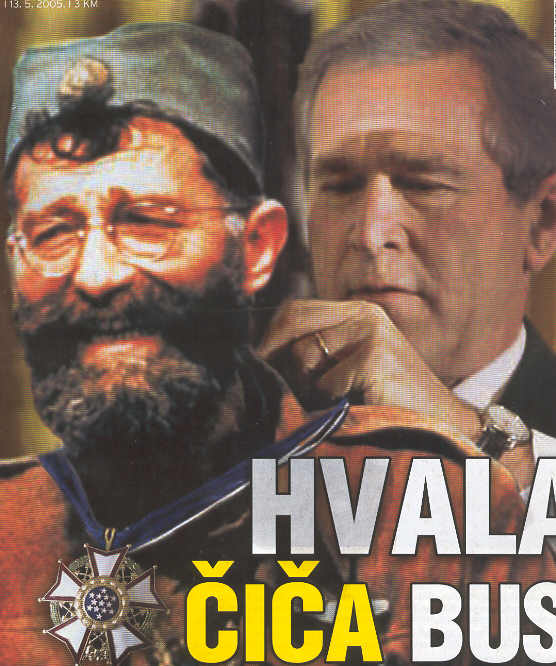

Adding insult to injury: Washington decorates a Nazi-collaborationist leader

by Marko Attila Hoare

The sixtieth anniversary of the defeat of Nazi Germany is not when one would expect the US government to decorate Nazi collaborators. Yet on 8 May 2005 a delegation of US war veterans posthumously presented the Legion of Merit to Serbia’s General Dragoljub ‘Draža’ Mihailović, leader of the ‘Chetnik’ movement during World War II; a convicted war criminal and Nazi collaborator. The award was originally made to Mihailović in 1948, two years after his execution by the Yugoslav authorities. But it is only now that the US has decided to hand over the award to Mihailović’s daughter. It is as if they had chosen the anniversary of VE day to present an award to Marshal Pétain, or to the Dutch policemen who arrested Anne Frank. The US action has provoked sharp protests from Bosnians, Croatians, Kosovars and Serbian anti-fascists. To understand this bizarre decision, the tangled threads leading up to it require some untangling.

Pact and coup

Yugoslavia entered World War II as an ally of the Third Reich. On 25 March 1941, Yugoslav prime minister Dragiša Cvetković and foreign minister Aleksandar Cincar-Marković signed a protocol making Yugoslavia a member of the Tripartite Pact, and therefore an ally of Nazi Germany. The Yugoslav government was bullied into signing this protocol by the Germans, despite the pro-Allied sympathies of most mainstream Yugoslav politicians - Serbs, Croats, Slovenes and others alike. Indeed, the Germans made it very clear to the Yugoslavs that the alternative to joining the Pact was war - one in which Yugoslavia would be easily pulverised by the Wehrmacht. Like other European statesmen since, Hitler had an exaggerated perception of Yugoslav military capabilities, and was ready to offer Belgrade relatively lenient terms: Yugoslav membership of the Pact would be a mere formality, not requiring actual military collaboration. This would have kept Yugoslavia effectively neutral during the impending German assault on Greece, forcing the Germans to attack the Greeks along the latter’s well defended border with Bulgaria - the so-called ‘Metaxas Line’. Such was the price Hitler was willing to pay to keep Yugoslavia quiet.

At this point, Winston Churchill and British intelligence carried out one of the most cynical Allied ploys of World War II: they conspired with a clique of Yugoslav air-force and army officers to execute a coup against the Yugoslav government, in the hope that this would bring Yugoslavia into the war on the Allied side. On the night of 26-27 March, therefore - as demonstrators in Belgrade and other Yugoslav cities marched under the self-consciously suicidal slogans ‘Better war than the Pact; Better the grave than a slave’ - the British-backed air-force and army officers seized power. The officers in question were scarcely anti-fascist: the coup organiser Borivoje Mirković kept a signed photograph of fellow aviator Hermann Goering on his desk; the new government released Serbian fascists imprisoned under the previous regime; and it appointed the former chairman of the German-Yugoslav and Italian-Yugoslav friendship associations to be its new foreign minister. Their coup was motivated in large part by Serb-nationalist hostility to the concessions made to Croatian autonomy by the previous regime. Such were Churchill’s chosen allies.

The Americans, for their part, had attempted before the coup - through both diplomatic and unofficial channels - to push Yugoslavia into a confrontation with Nazi Germany. In this context it was - in ironic contrast with the 1990s - the liberal interventionists in American politics who lauded and exaggerated Serbian military valour, deceiving themselves and others with their estimates of the Yugoslav Army’s ability to resist foreign invasion. American diplomacy systematically pressurised Yugoslav statesmen in order to deter Yugoslavia’s entry into the Pact, culminating with the freezing in March 1941 of Yugoslav assets in the US. Although playing a junior role in relation to the British, the Americans were nevertheless closely involved in encouraging the Great-Serb elements that staged the fateful coup. The American press’s euphoric reaction to the coup, as a blow against the Germans, may have helped convince the latter to attack Yugoslavia. Yet the US did not provide any actual military assistance to support the country its own diplomacy had placed in jeopardy: Roosevelt’s hands were tied by the anti-interventionist climate of opinion in the US, which neutralised effective American opposition to the Nazis.

Débâcle of royalist Yugoslavia

Ever since the coup, its various apologists have claimed that it involved ‘repudiation’ of the Pact. On the contrary: once in power, the new Yugoslav government reaffirmed Yugoslavia’s loyalty to the Tripartite Pact, assuring the Germans that the coup had not been directed against them, but merely represented the settling of internal Yugoslav scores. Yet Hitler, aware of British involvement in the coup, no longer trusted the Yugoslavs. Up until March 1941, Hitler had supported a united Yugoslavia; he now moved to destroy the country. The Wehrmacht invaded its Yugoslav ally on 6 April and, with some assistance from the Italians and Hungarians, totally defeated the Yugoslav Army in a mere eleven days and at the cost of a mere 151 German dead. Yugoslav resistance collapsed ignominiously. The country’s predominantly Serb generals subsequently sought to blame the disgraceful defeat on the ‘treachery’ of Croat troops: in fact, the Yugoslav command had anyway planned to abandon the Croatian and Slovenian north to the enemy and retreat into the interior, leaving the Croats and Slovenes in the lurch. Moreover, the Germans captured Belgrade by invading Serbia from the eastern Balkans and Hungary, not by going through Croatia, and captured the Yugoslav capital without a struggle: the Serb troops on this front proved to be as ‘treacherous’ as the Croats in the north. The reality was that neither Serbs nor Croats were particularly willing to die for the rotten and brutal Yugoslav state.

Churchill and Roosevelt therefore succeeded in dragging Yugoslavia into the war - at an eventual cost of one million Yugoslav dead, including about half a million Serbs and eighty per cent of the country’s Jewish community. The coup leaders of March were not among the dead: they fled Yugoslavia, leaving their fellow countrymen to bear the consequences of their actions. Yet Churchill had shot himself in the foot. The Wehrmacht, now able to attack through Yugoslavia, invaded Greece along an extended frontline, crushed Greek resistance and pushed the British Army in Greece into the sea. Various Greek and Yugoslav historians have since claimed that the German invasion of the Balkans resulted in a delay of several weeks to the launch of Operation Barbarossa, meaning that the Wehrmacht could not reach Moscow before winter set in. Ergo: Germany lost the war because of Greek and/or Yugoslav resistance in 1941. In fact, as historians such as Martin van Creveld and Bryan Fugate have shown, Barbarossa’s launch was delayed due to logistical problems unrelated to the Balkans; the campaign there did not affect it. Not only did Yugoslavia’s entry into the war speed the Greek defeat, but it allowed the Germans to transport their troops back into position for Barbarossa more quickly, across Yugoslav territory.

The Serbs, like other nations occupied by the Axis, were divided between resolute anti-fascist resisters, committed ideological quislings, and opportunists ready to collaborate with both Axis and Allies in pursuit of their own interests (this, of course, applied to the political classes: the mass of ordinary people sought above all to survive). Among the Serbs, the resisters were the Partisans under the leadership of Josip Broz Tito and the Communist Party of Yugoslavia; the quislings were the followers of the puppet prime minister General Milan Nedić and the fascist leader Dimitrije Ljotić; and the opportunists were Mihailović and the Chetniks. In practice, there was very little difference in behaviour between Nedić’s and Ljotić’s outright quislings and Mihailović’s Chetniks, who collaborated with the Nazis while seeking to crush the real resisters - the Partisans - and exterminate Muslims, Croats, Jews and others into the bargain.

‘Resistance’ and resistance

Mihailović was a Yugoslav Army officer and member of Borivoje Mirković’s conspiratorial circle of 26-27 March, who had taken to the hills following the Yugoslav capitulation, intending to continue the resistance. Yet his version of ‘resistance’ meant essentially waiting for the Allies to win the war on Yugoslavia’s behalf, then to fall upon the Germans after they had already been defeated. It was the Partisans who launched a genuine guerrilla resistance while the Chetniks were waiting in the wings. Faced, by the summer of 1941, with a rival and genuine resistance movement in the shape of the Partisans, Mihailović turned the Chetniks’ guns against his fellow Serbs, starting a civil war that would result in tens if not hundreds of thousands of dead. At the same time - already in the autumn of 1941 - Mihailović began making overtures to the Germans, seeking to reach an accommodation with them for joint action against the Partisans. This would have placed the Chetniks in the position of German anti-Communist auxiliaries, helping to suppress the genuine Yugoslav resistance while waiting for the Great Powers to determine the outcome of the war amongst themselves. That Mihailović failed to reach an agreement with the Germans at this time was not for want of trying on his part, but merely due to German unwillingness to deal with someone they considered a ‘rebel’.

Tito and the Partisan leadership were driven out of Serbia by the combined attacks of the Germans and Chetniks, and retreated to the neighbouring puppet state, the ‘Independent State of Croatia’ (NDH - Nezavisna Država Hrvatske). Hitler had supported a united Yugoslavia until March 1941, but following the Belgrade coup he decided to set up a Great-Croatian puppet-state - one that would include all of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Even so, he was less interested in Croatia than he was in Serbia - so Serbia was placed under exclusive German control, while the NDH was made an Italo-German condominium, a buffer state between the two Axis allies. The existence of the NDH is sometimes used by certain historical ignoramuses to ‘prove’ the existence of a traditional German interest in Croatia, one that supposedly explains the ‘German plot’ to engineer Yugoslavia’s break-up in the 1990s, in order to establish an independent Croatia as part of Germany’s ‘sphere’ in the Balkans. Pace such fantasies, the German establishment of the NDH was testimony to Hitler’s lack of interest in Croatia and Bosnia, and was to have serious repercussions for the development of an anti-fascist resistance.

Tito and Mihailović both mistakenly assumed that Serbia would form the epicentre of the Yugoslav resistance. In fact, Croatia and Bosnia turned out to be the epicentre, while Serbia became something of a backwater - and this for a number of reasons. The Nazis were unable to attract any mainstream or popular senior Croat politicians to serve as their quislings - the leadership of the principal Croat party, the Croat Peasant Party under Vladko Maček, refusing to collaborate. Consequently the Nazis were forced to rely on an extremist fringe movement, the ‘Ustashe’, under the leadership of Ante Pavelić. This was equivalent to placing the Ku Klux Klan in power in the USA. The Ustashe embarked on a genocidal policy of exterminating the Serb, Jewish and Gypsy populations of the NDH, killing hundreds of thousands and manufacturing a powerful Serb resistance virtually overnight. At the same time, the lighter German military control in the NDH than in Serbia meant that the rebels were not subject to such effective reprisals: simply put, it was more dangerous to remain passive in the NDH than in Serbia, but safer to resist.

National liberation

The third reason for the Partisans’ success in the NDH was their championing of the national liberation of both Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina, enabling them to win the support of Croats and Muslims as well as Serbs. Supporters of Slobodan Milošević have sought - with considerable success - to sell to the Western public the idea that it was only Serbs who fought as Partisans. The reality was very different. At the start of their uprising in 1941, the Communists appealed to the ‘freedom-loving Croatian nation, that has for centuries struggled against its oppressors’ to ‘expel the fascist occupiers and destroy the hateful puppet government of the traitor Pavelić’, promising that ‘from the ruins of the tyranny of the occupiers and the Frankists [Ustashe] will rise a free and independent Croatia in which there will be no trace of the Frankists’ and occupiers’ tyranny, plunder, evil chauvinism and racial insanity.’ Similarly the Communists referred to their Partisan forces in Bosnia-Herzegovina as the ‘People’s Liberation Army of Bosnia-Herzegovina’, which was ‘composed of Muslims, Croats and Serbs’ and which was fighting a ‘decisive, ferocious struggle for the national liberation of Bosnia-Herzegovina’.

The Croatian Communists were the most powerful wing of the Yugoslav Communist movement; Tito himself was a Croat from the Croatian heartland of Zagorje. By the end of 1943 - shortly after Tito and the Communists had proclaimed a new, federal Yugoslavia - the western Yugoslav lands were dominating the Partisan movement: of 97 Partisan brigades then in existence, 38 were from Croatia, 23 from Bosnia-Herzegovina and 18 from Slovenia. Of the 38 Croatian Partisan brigades, 20 had an ethnic-Croat majority, 17 an ethnic-Serb majority and 1 an ethnic-Czech majority. In Bosnia-Herzegovina, at this time, the Partisans were approximately two thirds Serb and one third Muslim and Croat, while the Slovene Partisans were overwhelmingly ethnic-Slovene. At the same time, the whole of eastern Yugoslavia (Serbia, Vojvodina, Montenegro, Kosovo and Macedonia) was contributing only 18 Partisan brigades. Half a century later, Partisan veterans would lead Croatia during its transition from Communism and in its war of independence: Franjo Tuđman as president, Josip Manolić as prime minister, Martin Š pegelj as defence minister and founder of the Croatian Army, Josip Boljkovac as interior minister and Janko Bobetko as Croatian Army chief of staff. This did not prevent Milošević supporters from denouncing Croatia as ‘Ustasha’ - even as they resurrected the policies of Serbia’s own Nazi collaborators.

Collaboration, genocide and anti-semitism

While the Partisans fought the occupiers, the Chetniks collaborated. Mihailović’s officers in the NDH served as auxiliaries of the Italians, who unlike the Germans had no qualms about collaborating with rebels. Furthermore, various Bosnian Chetnik commanders signed treaties of cooperation with the very Ustasha state that had exterminated hundreds of thousands of their fellow Serbs. Mihailović himself was careful not to put his signature on incriminating documents of this kind, but he never repudiated his own officers who did so. Meanwhile, under the military umbrella provided by their Italian allies, the Chetniks engaged in a genocidal campaign of their own against Muslims and Croats, in order to lay the foundations for a ‘Great Serbia’. Petar Bacović, Mihailović’s commander for eastern Bosnia-Herzegovina, reported in September 1942, that ‘our Chetniks - greatly embittered by the misdeeds committed by the Ustashe against the Serbs - skinned alive three Catholic priests between Ljubinje and Vrgorac. Our Chetniks have killed all men aged fifteen years or above. They did not kill women or children aged under fifteen years. Seventeen villages were entirely burned... We shall soon, God willing, attack Fazlagić Kula, the last Muslim stronghold in Herzegovina. After that in Herzegovina there will not remain a single Muslim in the villages.’ Pavle Djurišić, commander of the Lim-Sanjak Chetnik Detachment, reported to Mihailović on 13 February 1943 the results of the Chetnik actions in the Pljevlja, Foča and Čajnice districts: ‘All Muslim villages in the three mentioned districts were totally burned so that not a single home remained in one piece. All property was destroyed except cattle, corn and senna.’ Furthermore: ‘During the operation the total destruction of the Muslim inhabitants was carried out regardless of sex and age.’ In this operation, ‘our total losses were 22 dead, of which 2 through accidents, and 32 wounded. Among the Muslims, around 1,200 fighters and up to 8,000 other victims: women, old people and children.’

Mihailović’s Chetnik movement was viciously anti-Semitic. Bacović claimed in October 1942 that ‘the Jews, associated with much of the scum of the earth, fled to our country and began to propagate such a better and happier state of affairs in a Communist state.’ Dobroslav Jevđević, Mihailović’s political representative in eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina, claimed in June 1942 that Partisan units were largely made up of ‘Jews, Gypsies and Muslims’. The following month, he accused the Partisans: ‘They have destroyed Serb churches and established mosques, synagogues and Catholic temples.’ A pamphlet distributed by the Chetniks around Sarajevo in the autumn of 1942 spoke of ‘the Communists, whose leaders are Jews and who wish to impose Jewish rule on the world’. A Chetnik proclamation of September 1942 claimed that ‘an Ustasha, German, Jew or Gypsy may become a Partisan; in other words anyone willing on behalf of the foreigner to participate in the slaughter and killing of the best Serb sons.’ A group of senior Chetnik commanders issued a proclamation in February 1943 to the Serbs of Croatia and Bosnia, claiming that ‘since we have cleansed Serbia, Montenegro and Herzegovina, we have come to help you to crush the pitiful remnants of the Communist international, criminal band of Tito, Moše Pijade, Levi Vajnert and other paid Jews’. They called upon the Partisan rank-and-file to ‘kill the political commissars and join our ranks right away’, like the ‘hundreds and hundreds who are surrendering every day, conscious that they have been betrayed and swindled by the Communist Jews’. The 9 March 1943 issue of the Chetnik newspaper Vidovdan described the Partisans as ‘bandits led by the Zagreb Jew "Tito" and the Belgrade Jew Mose Pijade’.

Mihailović himself informed his subordinates in December 1942: ‘The units of the Partisans are filled with thugs of the most varied kinds, such as Ustashe - the worst butchers of the Serb people - Jews, Croats, Dalmatians, Bulgarians, Turks, Magyars and all the other nations of the world.’ On a previous occasion he had stated ‘I have never made a genuine agreement with the Communists, for they do not care about the people. They are led by foreigners who are not Serbs: the Bulgarian Janković, the Jew Lindmajer, the Magyar Borota, two Muslims whose names I do not know and the Ustasha Major Boganić. That is all I know of the Communist leadership.’ Nor did Chetnik anti-Semitism stop at words. As Israel Gutman’s Encyclopedia of the Holocaust notes: ‘There were many instances of Chetniks murdering Jews or handing them over to the Germans.’

Chetnik chauvinism and genocide were motivated by the desire to create a Great Serbia. A Chetnik pamphlet issued in 1941, endorsed by Boško Todorović, Mihailović’s most senior commander in Bosnia, explained the Chetnik goal: ‘When it achieves freedom, a golden Serb freedom, then the Serb nation will - freely and without bloodshed, by means of the free elections to which we are accustomed in the Serbia of King Peter I - take its destiny into its own hands and freely say whether it loves more its independent Great Serbia, cleansed of Turks and other non-Serbs, or some other state in which Turks and Jews will once again be ministers, commissars, officers and "comrades".’

Britain and Yugoslav resistance

As early as the autumn of 1942 Colonel Hudson, a British agent sent to make contact with the Yugoslav resistance, reported that Mihailović had agreed ‘to adopt the policy of collaboration with the Italians pursued by the Montenegrin Chetniks’. Another British agent, Colonel Bailey, reported that Mihailović had made a speech in his presence in February 1943, at which he (Mihailović) complained that the ‘Serbs were now completely friendless’ and that the ‘English were now fighting to the last Serb in Yugoslavia’, with no intention whatsoever of helping them. Consequently, ‘so long as the Italians remained his sole adequate source of benefit and assistance generally, nothing the Allies could do would make him change his attitude toward them’ - i.e. cease collaboration. So far as Mihailović was concerned, ‘his enemies were the Partisans, the Ustashe, the Muslims and the Croats. When he had dealt with them, he would turn to the Italians and Germans.’ In the crucial Battle of the Neretva that took place at this time, at which the Partisans succeeded with great difficulty in breaking out of Axis encirclement, the Chetniks fought on the Italian side. On this basis, the British gradually shifted their support from the Chetniks to the Partisans, finally ending all contact with Mihailović in 1944 and designating Tito the sole leader of the Yugoslav resistance. Conversely, following the Italian capitulation in the summer and autumn of 1943, the Germans shifted their policy and began to collaborate directly with the Chetniks.

Apologists for Mihailović and anti-Communist conspiracy theorists have claimed that the British decision to drop him was the work of Communist moles in British intelligence. Churchill’s decision was based, however, not only on the reports of his agents in the field, but on his own interception of German intelligence information that used the Ultra code. The conspiracy theorists allege that the intelligence reaching Churchill was filtered by Communist moles to create a false picture of which Yugoslav group was resisting and which was collaborating. Yet although there were undoubtedly Communists in British intelligence at the time, the conspiracy theorists have so far failed to unearth a single shred of evidence in support of the existence of an actual conspiracy to skew Churchill’s perception of events in Yugoslavia. Indeed Stalin in this period was mortally afraid of engaging in any kind of subversive activity that might alienate the Western Allies, and was consequently deeply wary of Tito’s revolutionary actions. As the American historian Walter R. Roberts writes: ‘The Soviets showed surprisingly little interest in their Communist allies in Yugoslavia and, because they did not wish unnecessarily to disturb relations with the British and US Governments, they supported the [royalist] Yugoslav Government-in-Exile until well into 1943.’ And the ubiquitous Communist moles were hardly likely to annoy Stalin by pursuing an independent pro-Tito policy of their own (James Klugman, the conspiracy theorists’ favourite culprit among the Communists in the British intelligence establishment, was to become one of Tito’s most virulent critics following the Tito-Stalin split of 1948). The irony is that it was Churchill, not Stalin, who took the lead in shifting Allied support to Tito. On this occasion, Churchill’s hardheaded anti-Nazi realism and his romantic identification with the Partisans combined to trump his anti-Communism. Had the Chetniks won the Yugoslav civil war, they would have plunged Yugoslavia into a bloodbath as they sought to exterminate non-Serbs in their efforts to create a Great Serbia. Churchill thus redeemed himself somewhat, following his earlier blunder in dragging Yugoslavia into the war.

Mihailović rewarded

Mihailović continued his opportunistic game of seeking to collaborate with both Axis and Allies. In this context, he assisted the US airborne evacuation of some two hundred and fifty airmen (forced to bail out after raids on Romania’s oil fields) from Chetnik territory in August 1944. This simply meant that the Chetniks allowed the Americans to use their airstrip for the evacuation - scarcely a particularly heroic action - while at the same time Mihailović sent a delegation along with the departing US planes in a fruitless effort to win back Allied support. Yet it was for the rescue of US airmen that Mihailović would posthumously receive the Legion of Merit. On other occasions, however, Mihailović’s Chetniks rescued German airmen and handed them over safely to the German armed forces. Were he so inclined, Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder could follow Washington’s example and decorate Mihailović for saving the lives of his country’s servicemen. Yet none of Mihailović’s intrigues saved him or his Chetnik movement from destruction at the hands of the victorious Partisans. The revolution in the western Balkans - Europe’s second and last successful Communist revolution - succeeded thanks to British and American military intervention, which enabled the re-establishment of Yugoslavia. This is a fact that Milošević’s left-wing supporters usually prefer not to mention.

The Americans, with a weaker intelligence presence in the Balkans than the British, were less in touch with the realities of the Yugoslav civil war. They were consequently less than enthusiastic about British abandonment of the anti-Communist Mihailović, and more reserved toward the Partisans. On 29 March 1948, at the height of the Cold War, US President Truman posthumously awarded Mihailović the Legion of Merit for his role in rescuing American airmen. This was at a time when Tito was still Stalin’s loyal henchman in Eastern Europe, and pursuing a confrontational policy toward the Western powers in Greece and elsewhere. Within months, however, the situation had changed: Stalin broke with Tito, whom the Western powers once again began to support - this time as a bulwark against the Soviet Union. Consequently the Americans refrained from making public their award to Mihailović until 1967, and refrained from presenting his daughter with the award until this year.

The Bush Administration’s readiness to overturn American diplomatic tradition in this way should perhaps come as no surprise from an administration that has made a habit of overturning diplomatic tradition, for better or for worse. One of the Administration’s first diplomatic initiatives, following Bush’s recent re-election, was to recognise the Republic of Macedonia under its rightful name, delivering a well-deserved slap in the face to Greece, thanks to whose merciless chauvinistic bullying Macedonia has been forced to labour under the clumsy official denomination of ‘Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia’ since its independence in the early 1990s. The Bush Administration thereby rewarded a loyal ally, and may have felt that the presentation of the award to Mihailović was a similarly harmless gesture of solidarity to the post-Milošević regime in Serbia-Montenegro, whose preposterous foreign minister Vuk Drašković has combined a quixotic attachment to the Mihailović legend with a sincere desire to improve relations with the West. Yet so far as the peoples of Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia and Kosovo - and, of course, many anti-nationalist Serbs - are concerned, the US has thereby rewarded an architect of the same genocidal Great Serbian project that has brought them such misery, in the 1990s as in the 1940s. As on previous occasions, an ill-conceived piece of realpolitik has had negative results: in this case, an insult to add to the grievous injuries of the peoples of the former Yugoslavia.

Marko Attila Hoare’s Partisans and Chetniks will be published shortly by Oxford University Press as a British Academy monograph

*****

IN BOX

On 9 May 2005, on the occasion of the sixtieth anniversary of the victory over fascism, a delegation of US war veterans handed over to the daughter of General Dragoljub (Draža) Mihailović in Belgrade the Legion of Merit awarded him fifty-seven years ago by President Harry Truman. According to unofficial sources, the medal was handed to Dr Gordana Mihailović in the US residency on Dedinje [Belgrade] in the strictest secrecy. As the Serbian press reports, at her request the award of the medal was attended neither by Draža’s grandson Vojislav Mihailović nor by Vuk Drašković, the foreign minister of Serbia/Montenegro and leader of the SPO [Serb Renewal Movement], although these gentlemen had conceived and announced the whole business quite differently.

For Draža’s grandson expected to accept the distinction himself in his grandfather’s name, while Vuk Drašković would not have refused such a role either, declaring that it would have been an extraordinary honour for him. The medal was intended to be handed over to them by the US ambassador to Serbia/Montenegro, Michael Polt, in a commemorative ceremony in Belgrade.

It is interesting that precisely in this past year a historic reconciliation has been proclaimed in Serbia/Montenegro. For on 21 December 2004 the Assembly of Serbia equalized the status of Chetniks and Partisans. The session at which this was decided was presided over by the Assembly’s vice-president Vojislav Mihailović, Draža’s grandson, and the law was put forward as a matter of urgency by the deputies of the SPO.

According to the modified law, all those who from 17 April to 31 December 1941 joined the ranks of the Ravna Gora movement have the right to a Ravna Gora commemorative medal, and in every way they will be made equal with holders of the Partisan commemorative medal. Even those who were sentenced for having taken part in fighting against Partisan units will have this right. That means the holders of the medal will have regular monthly pensions, family allowances, contributions to funeral expenses... and the funds for these will be guaranteed from the budget of the Republic of Serbia.

In Croatia, the president of the Civic Council for Human Rights, Zoran Pušić, sent an open letter to the US ambassador to Zagreb, Ralph Frank, explaining that: ‘the decision from the days of President Truman was taken without the knowledge of certain facts - that the Chetnik movement had collaborated with the armies of Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany.’

B-H Presidency member Sulejman Tihić likewise protested, telling US ambassador to Sarajevo Douglas McElhaney that: ‘the handing over of this award will put a serious blot on everything positive that the United States has done up to now for B-H’.

Extracts translated from a report by Dragana Todorović in Dani (Sarajevo), 13 May 2005

***

IN BOX

‘This is a mistake that will be paid for over many years exclusively by the population of Bosnia-Herzegovina, above all because the modern-day Chetniks have understood the honouring of Draža Mihailović as an award given to themselves. And quite rightly so: what they did in this last Bosnian war differs in no way from the crimes committed by Mihailović’s forces in the previous one - even though it is true that they were then not called ‘Srebrenica’ but ‘Foča’. In February 1943 the Chetnik vojvoda [warlord] Pavle Djurišić reported with pride to Mihailović the results of an operation in the Pljevlja, Foča and Čajnice districts: ‘During the operation the total destruction of the Muslim inhabitants was carried out regardless of sex and age... our total losses were 22 dead, of which 2 through accidents, and 32 wounded. Among the Muslims, around 1,200 fighters and up to 8,000 other victims: women, old people and children.’

Only a few months after placing the SDS leadership - the political heirs of the Chetnik movement - on the black list, the current US administration is once again treating them to a favourable wind. Quite apart from the fact that such a move makes US policy towards B-H exceptionally inconsistent and absurd, our domestic revisionists have been given the final confirmation needed for a thoroughgoing re-working of history. By virtue of this act, a small and essentially criminal organization has been put on the same level as the true heroes of resistance to Nazism; doubtless it will not be long before our domestic far right once again proposes a ‘historic reconciliation’ of Chetniks and Partisans. Any prospects for a more serious consideration and contextualization of the role of the Chetnik movement in the region have been totally destroyed. The historical continuity Dragoljub Mihailović - Radovan Karadžić has now received legitimation of a kind that no one could have imagined.’

Emir Suljagić, Dani (Sarajevo), 13 May 2005

***

IN BOX

‘I was really shocked and disappointed when this medal was handed over: after all the time that has passed, this is the worst possible moment for this. In the light of what we know today, and which the US government should have known - i.e. that the forces led by Mihailović carried out atrocities against Muslims, Croats and others in Bosnia - the decision to hand over the award was clearly inexplicable. I hope that most people in Bosnia-Herzegovina will understand that this was the action of an administration which seems totally out of touch both with what is happening in this part of the world and with what I believe the American people for the most part feels about Bosnia - i.e. basically sympathy and understanding.’

Robert Donia, interviewed in Dani (Sarajevo), 13 May 2005

|