|

The acquittal of Sefer Halilovic

by Ivan Lovrenovic

This is not the first time that the court in The Hague has dropped charges against a defendant, but the freeing of Sefer Halilović rightly draws special attention. Quite apart from anything else, Sefer Halilović was the first commander of the Army of Bosnia-Herzegovina. But in addition, over the past twelve years this retired general, having become a victim of a shameful conspiracy, was the target of so many false accusations and vicious intrigues that his triumphal return from The Hague does indeed appear as a kind of a happy ending to some sinister political crime thriller. It had beev the intention of certain Sarajevo circles, who participated from the shadows in supplying ‘evidence’ for the charges against him, that he should play the role of a sacrificial lamb.

The intention was to crush and definitely end the process of establishing the command responsibility for war crimes among Bosniak military and political leaders. As was subsequently learned, not even Alija Izetbegović himself was excluded from this process. Halilović’s release changes everything. The investigation into Izetbegović ended, of course, with his death, but The Hague is preparing to try Halilović’s successor, General Rasim Delić. In line with the concept of command responsibility, Halilović had been charged with practically all the crimes committed by Bosnian soldiers, including the foreign mujahedeen. It is indicative that a couple of weeks before the verdict on Sefer Halilović, the prosecution asked that the indictment of General Delić be broadened to include the crimes committed in Grabovica and Uzdol - of which, as the Tribunal has now decided, Halilović was unjustly accused. The intention was to crush and definitely end the process of establishing the command responsibility for war crimes among Bosniak military and political leaders. As was subsequently learned, not even Alija Izetbegović himself was excluded from this process. Halilović’s release changes everything. The investigation into Izetbegović ended, of course, with his death, but The Hague is preparing to try Halilović’s successor, General Rasim Delić. In line with the concept of command responsibility, Halilović had been charged with practically all the crimes committed by Bosnian soldiers, including the foreign mujahedeen. It is indicative that a couple of weeks before the verdict on Sefer Halilović, the prosecution asked that the indictment of General Delić be broadened to include the crimes committed in Grabovica and Uzdol - of which, as the Tribunal has now decided, Halilović was unjustly accused.

This is roughly speaking the context for judging the significance of the tribunal’s decision on the one hand and Sefer Halilović’s brilliant personal victory on the other. The reaction of our politicians and political bodies to the news has displayed their usual moral shallowness and political immaturity. The reactions of the Croat and Serb ‘bloc’ were reduced to the old standard complaint that The Hague tribunal is politically motivated and nationally biased. The reaction of the Bosniak political establishment was naturally different. The court’s decision was praised as ‘another proof of the honourable struggle for the preservation of an integral, united and multi-ethnic Bosnia-Herzegovina’; as ‘confirmation that the Army of Bosnia-Herzegovina did not commit the crimes the other sides committed’; and even, according to Haris Silajdžić, as proof that the war was ‘organised aggression and genocide, not a civil war’. The president of the SDA, Sulejman Tihić, was more measured. He stated that the court in The Hague ‘has confirmed that it was a matter of individual criminal acts for which local AB-H commanders were responsible, while on the part of the Army of Bosnia-Herzegovina itself, i.e. of the legitimate Bosnian government, there was no systematic encouragement, planning, approval or toleration of war crimes.’

In all such reactions, it is striking that the real context of the living human being who became a victim gets lost, that his personal tragedy and that of his family is passed over in silence, while the essential meaning of the justice that he himself had struggled to establish is made into an abstract category. All that is left is a political-ideological discourse motivated by, and addressed to, different concerns. It overlooks the fact that Sefer Halilović’s career itself offers dramatic evidence for a different interpretation of what actually happened, and that one should perhaps wait for Rasim Delić’s trial before issuing generalised statements of this kind. The inhumanity of these reactions is best testified to by the fact that they say nothing whatsoever either about the victims of the massacres.

Towards an ethnically pure Army

What did the court actually establish in its verdict that Halilović should be freed? That crimes were committed against the Croat inhabitants of Grabovica and Uzdol on respectively 9 and 14 September 1993; that at that time Sefer Halilović was no longer a commander with the relevant responsibility, but a notional inspector without proper authority; and that the local commanders, Zulfikar Ališpago and Enver Buza, were subordinate to the new commander, Rasim Delić. The latter was appointed commander of the B-H Army by Alija Izetebegović in place of an increasingly distrusted Sefer Halilović on 8 June 1993, i.e. three months before the massacres in Grabovica and Uzdol. Independent reporters and analysts have long ago established the ideological and evolutionary implications of this change and that date in the history of the Army of Bosnia-Herzegovina. They agree that this change of personnel at the top of the armed forces was necessary in order to begin the systematic ideological and ethnic transformation of the Army into a Muslim and Bosniak one. The consequences of this were soon visible.

Such truth as the statements cited earlier may contain is valid only perhaps for the Army at the time of Halilović’s active command, and for the nature of the war in that period. It is not that no crimes were committed at this time against non-Bosniak populations, but that the perpetrators were then systematically pursued in order to arrest and punish them, while the Army behaved in accordance with the principles contained in the famous Platform of the Bosnia-Herzegovina Presidency of April 1992, which declared that it was fighting a war for the defence of a multi-ethnic state of equal peoples and citizens. That was a truly heroic period, when the Army was commanded by generals such as Jovan Divjak and Stjepan Š iber, whose unwavering loyalty to Bosnia-Herzegovina scandalised the proponents of ‘pure’ Croat and Serb ideas (and, as it soon turned out, their Bosniak equivalents as well).

As for Halilović, one can say only that he was a fanatical adherent of such a Bosnia-Herzegovina, representing it in the accented ideological and political discourse typical of the old JNA officer cadre, thus crossing the line which a professional soldier should respect. Soon after his demotion he suffered a family tragedy that has remained unexplained to this day (as is true for many Sarajevo murders, including those of Nedžad Ugljen and Jozo Leutar). His wife and her brother were killed during an attack on Halilović’s flat on 7 July 1993, while his young son survived only by a miracle. There is abundant evidence that the bomb was placed by Halilović’s enemies in Sarajevo military intelligence. Halilović’s son Emir is about to publish a book, State Secret, which reconstructs in detail what happened on that day, written on the basis of material he has collected during the past twelve years. There is great interest in this book in Sarajevo.

Hunting Halilović

The pursuit of Halilović did not end then. Organised by great masters of the craft, former highly placed KOS officers who entered Izetbegović’s service (Fikret Mulimović, Jusuf Jašarević, etc.), a large-scale diversionary operation started soon after the massacres in Grabovica and Uzdol, which was largely responsible for Halilović’s indictment by the court in The Hague in 2001.

After having been retired by Izetbegović (in a slovenly, ignoble and humiliating fashion), Sefer Halilović turned to politics. He founded the Bosnian Patriotic Society and became its president. Lacking much political experience and knowledge, he led it ‘with his heart’. His public rhetoric consisted of advocacy of a multi-ethnic Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina, combined with a fiery critique of Alija Izetbegović. The party initially appeared a fresh plant in the grey post-Dayton political landscape, only virtually to disappear after Halilović’s indictment and subsequent withdrawal from public life.

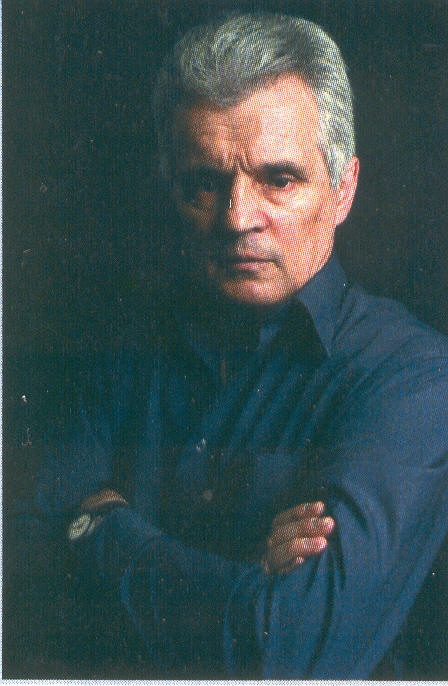

On his return from The Hague - where presiding judge Liu displayed an evident sympathy as he read out the acquittal, listening to which Halilović was unable to control his features - the freed man gave an hour-long TV interview. This was a wholly new Halilović, proud of his victory but also very focused, self-controlled and tempered. Politically, however, he has remained loyal to his initial beliefs. One could see that he has also mastered the new political ‘correctness’, in that he found a moment to declare himself a practising Muslim. At the end of the programme everything fell into a place. Asked whether, after all that had happened, he planned to engage once again in politics, Halilović answered: ‘If I do not engage in politics, politics will engage with me. Yes, I will.’

One can bet that on that night many in Sarajevo held fraught meetings. In the political setting which is starting to quicken and change, and in which many fine promises are increasingly being recognised as mere lies, the reappearance of Halilović - now greatly strengthened by the aura of an innocent man - could lead to a real earthquake on the Bosniak political scene. And the elections are only a year away.

Translated from Feral Tribune (Split), 25 November 2005

|