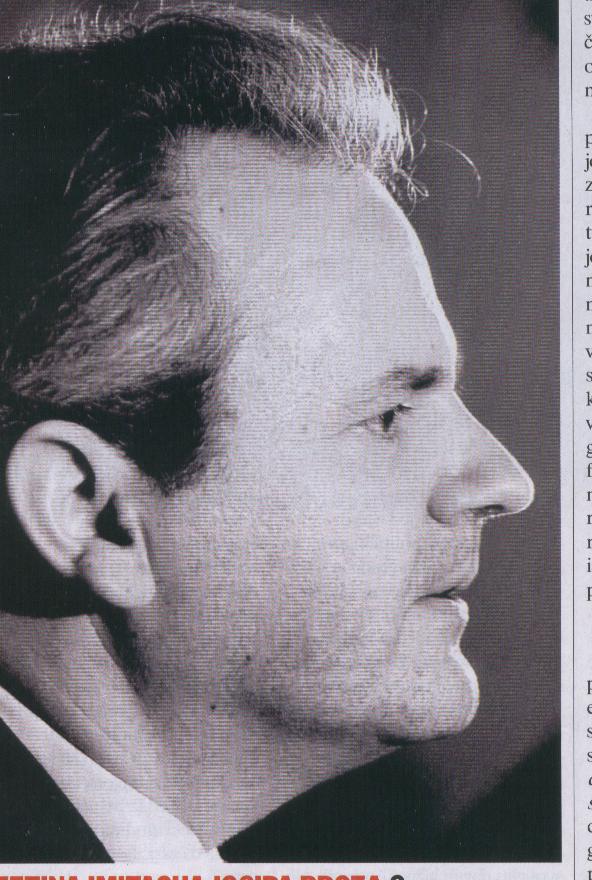

The butcher is dead

by Brendan Simms

Although he had sworn that he would never be taken alive, when the time came Slobodan Milošević went quietly with the Serbian commandos tasked with his extradition from Belgrade in June 2001. Death came to him yesterday, however, alone in his cell at the Hague. Although he had sworn that he would never be taken alive, when the time came Slobodan Milošević went quietly with the Serbian commandos tasked with his extradition from Belgrade in June 2001. Death came to him yesterday, however, alone in his cell at the Hague.

Many will feel that, by dying before final judgment could be passed at his war-crimes trial, Milošević has somehow ‘cheated the hangman’. Some will be relieved, perhaps including the current Serbian leadership.

The Americans, who did more than any other country to frustrate Milošević but whose relationship to the concept of international justice is increasingly fraught, will have mixed feelings. Others still will welcome the end of an expensive spectacle that served to remind the international community of its failures during the 1990s.

Yet the unfinished trial has achieved much. The evidence it threw up established clearly that Milošević was the inspiration for the ‘joint criminal enterprise’ to carve an ethnically pure ‘Greater Serbia’ out of the ruins of Bosnia and Croatia.

Over time, the prosecution case has also had a therapeutic effect on Serbian politics. There were many who sympathized with their former leader. But the recovery of refrigerated lorries with Albanian corpses and the harrowing footage of paramilitaries from Serbia engaged in atrocities at Srebrenica turned the majority against him.

Milošević was born in the Serbian town of Pozarevac on 20 August 1941, into a world of violence. The Germans were on the verge of unleashing a counter-insurgency campaign that left hundreds of thousands of Serbs and virtually the entire Jewish population dead.

Milošević’s parents, both teachers, were depressives who eventually committed suicide. Their son will be remembered as the man who bears the greatest individual responsibility for the collapse of the former Yugoslavia and the massacres that resulted. Most of these were not spontaneous popular combustions, but a carefully planned assault sponsored by Belgrade.

The directing spirit

We have long known from his co-conspirators, from intercept evidence, and from many other sources that Milošević was the directing spirit behind the early and decisive stages of ethnic cleansing in Bosnia during the spring and summer of 1992, when hundreds of thousands of Muslims and Croats were driven from their homes by Serbian paramilitaries.

More recently, evidence has surfaced to link him, or at least his security apparatus, to the Srebrenica massacre of 1995 in which about 8,000 Muslim men and boys were slaughtered. Milošević’s responsibility for the expulsion of more than one million Kosovar Albanians in 1999 is indisputable.

Yet he was a paradoxical figure. He does not seem to have been a xenophobic nationalist in any meaningful sense. There was no trace of racism in his personal dealings. In the 1980s he tried hard to match his wayward daughter to a dynamic young socialist of Turkish Muslim extraction. One of his closest cronies, Mihaly Kertes, was an ethnic Hungarian. His eccentric wife Mira Markovic, often seen as a Lady Macbeth figure, was a critic of Serbian nationalism.

Milošević’s fateful championship of Serbian nationalism was primarily motivated by political opportunism. As the legitimacy of the Yugoslav communist party waned after the death of Tito, the former dictator, in 1980, Milošević reinvented himself as the avatar of Serbian nationalism.

The tension between Serbs and the majority ethnic Albanian population in the southern autonomous republic of Kosovo provided him with the ideal opportunity. In 1987, in an impromptu televised address that made his reputation overnight, Milošević promised Serbian demonstrators in Kosovo that ‘no one will dare to beat you again’.

In subsequent years he made a determined effort to turn the Yugoslav federation into a ‘Serboslavia’ under his control. First, in the late 1980s, Milošević abolished the autonomy of Kosovo and Vojvodina within Serbia. A compliant government was installed in Montenegro. This process was characterized by much intimidation but little actual violence.

In the next stage, 1990-91, Slovenia and Croatia were left with no choice but to accept subordinate status or to bale out of Yugoslavia. Both managed to extricate themselves, Croatia with great bloodshed.

Facing the same choice, the Bosnians would have preferred to remain in a federal Yugoslavia if Milošević had not made life unbearable for them. Their bid for independence gave him and his Bosnian Serb proxies a pretext to launch a long-planned campaign of ethnic displacement in 1992.

The secret of his success was that he reflected Serbian opinion as much as he manufactured it. Virtually the entire Serbian intelligentsia, security forces and bureaucracy were more or less complicit in his policies. Many Serbs, especially the worse-off, kept faith with him to the end.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing was the hold he exercised over Western politicians. He had spent time in the US as a banker in the 1970s. He spoke good English, joshed with businessmen and diplomats over a glass of whisky, and generally stood out among the stony-faced antagonists of the Bosnian war as a genial and pragmatic figure. Milošević was a man they could ‘do business with’, a Yugoslav Gorbachev, who would lead his country westwards.

No Western establishment was more mesmerized by him than that of Britain. David Owen, a former foreign secretary and European Union representative at the peace talks in Geneva, described him as a man who ‘lives in the real world’. At the height of the Bosnian war in 1993 Owen said Milošević was ‘heading towards leading Serbia back into the European family’.

British idée fixe

Working with Milošević became an idée fixe of British policy. Diplomats in Belgrade were instructed, as one put it, to ‘get inside Milošević’s head and find out what his real bottom lines were’. To many, it seemed he got inside the British official mind instead.

This focus on Milošević was not just personal but structural. Old Balkan hands in Whitehall were, according to the late diplomat Sir Reginald Hibbert, ‘historically committed to Yugoslavia and to Serbia as the dominant component of Yugoslavia’. They had a ‘general, inherited, belief . . . that Serbia held the key to stability in the Balkans’.

British policy was at first disinclined to promote internal opposition to Milošević. This was partly on the defensible grounds that his successor might be more radical still, but primarily because of an unshakeable belief that Milošević was a force for stability who could ‘deliver’.

Even after the 1995 Dayton peace deal that brought an end to the Bosnian war, key figures of British Bosnia policy put their money on Milošević. Douglas Hurd, the former foreign secretary, and Dame Pauline Neville-Jones, former political director of the Foreign Office, represented NatWest Markets in talks with him in 1996 over the privatization of Serbian utilities.

Neville-Jones spoke of ‘an opportunity for Milošević to get himself into better standing again by modernizing, democratizing and dealing with the Kosovo problem’. Hurd argued that ‘Milošević had a window after Dayton. He could have turned back, in which case he could have been rehabilitated’.

This, of course, presupposed that Milošević was capable of so acting. There was never any likelihood of that. As one Foreign office source remarked: ‘We all knew Milošević was the biggest part of the problem right from the outset. But what took longer for us to get was that he could never also be part of the solution.’

The Americans, though generally clearer-headed about Milošević and his culpability, were not immune either. There was a grudging respect for him even from his nemesis, Richard Holbrooke, the negotiator who ‘cut a deal’ with him at Dayton and presented him with the final fatal ultimatum before the Kosovo war.

It was only in 1998-99, when Milošević reacted to Albanian guerrilla tactics in Kosovo with large-scale repression, that the West finally ended its long courtship and took up arms against him.

In the closing days of the Kosovo war key intelligence was passed to the international war-crimes tribunal, enabling the indictment that ultimately put him in the dock. And it was only then that Western governments and intelligence agencies began to take the Serbian opposition seriously, and to provide the kind of technological assistance that made the events of 2000 possible.

Milošević’s fall was swift: a contested election defeat in September 2000, followed by the Serbian revolution that swept him from power and nine months later into the prison cell where he died.

Brendan Simms is a trustee of The Bosnian Institute, a fellow in history at Peterhouse, Cambridge and the author of Unfinest Hour: Britain and the Destruction of Bosnia (2000). This op-ed appeared in The Sunday Times, 12 March 2006

|