|

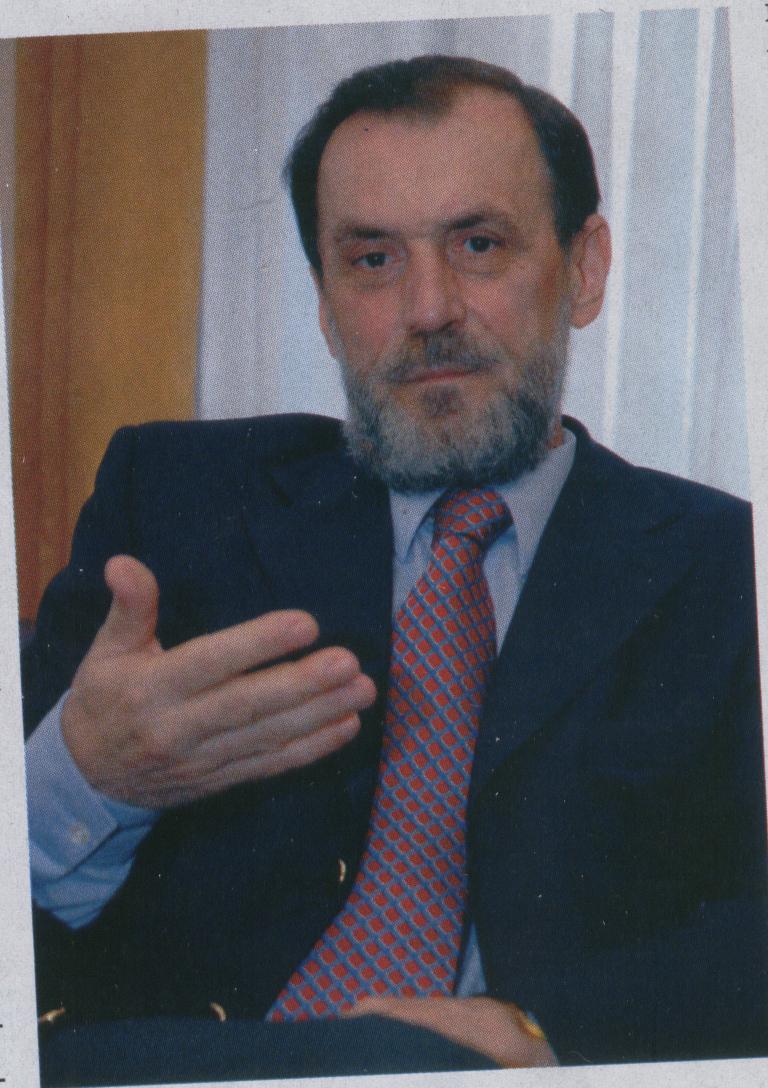

Vuk Draškovic - another hero of our time

by Mirko Kovac

Vuk Drašković is today the foreign minister of Serbia and Montenegro, a writer and the leader of a political movement. He is also an old acquaintance of mine. It is not my intention to blacken him here, merely to present some facts about him. He is after all not exceptional. Though I met him for the first time at the start of the 1990s, my story begins some fifteen years earlier when that capricious little beast scratched me with his red claws, and in doing so - herein lies the irony - helped me to acquire something of a reputation among people who do not care much for anyone’s reputation. Vuk Drašković is today the foreign minister of Serbia and Montenegro, a writer and the leader of a political movement. He is also an old acquaintance of mine. It is not my intention to blacken him here, merely to present some facts about him. He is after all not exceptional. Though I met him for the first time at the start of the 1990s, my story begins some fifteen years earlier when that capricious little beast scratched me with his red claws, and in doing so - herein lies the irony - helped me to acquire something of a reputation among people who do not care much for anyone’s reputation.

Raised from the dust

It all began in January1974, when I landed up in Belgrade’s Central Prison at the same time, as it turned out, as both I and a collection of my poems became the targets of a hostile campaign. My imprisonment, however, was caused by a love affair and a fight in the Writer’s Club, which was far better for me than if I had been gaoled for some political misdeed - the usual accompaniment of such campaigns. I spent my first night in an isolation cell, but on the following day was transferred to a cell containing sixteen prisoners, mainly petty criminals: burglars, pickpockets, gamblers, etc. As soon as I entered they read me the code of conduct, and asked me why I had been nicked. I told them all that had happened before the fight took place, the whole history of the adultery and how it had led to fisticuffs in the Club. When I told them I was a writer, no one believed me. Their image of writers was quite different, and quite apart from that no one had ever heard of me. They watched me suspiciously before subjecting me to interrogation. Had I ever published a book and if so of what sort? A shabby ‘stonecutter’ (slang for a convict who keeps coming back to prison) then rose up on his bed; an authority on literature, he silenced the ignoramuses before informing me that he had read Spartacus at least ten times and was an expert on novels. He demanded that I tell him the titles of my books, which I did, reluctantly but obediently. Silence fell. The ‘stonecutter’ snubbed me with a: ‘Never heard of them!’ I felt like a liar. But on the following day an unexpected change occurred: my reputation suddenly grew, I emerged from anonymity, while my petty criminal room-mates came to view me as a political prisoner, a dissident and opponent of a police state. I was raised to this pedestal, if only briefly, by Vuk Drašković.

Enemy of the State

This is how he did it. The prisoners could buy newspapers in the canteen, though the choice was limited. But a weekly called Revija 92 was freely distributed to all the cells. It was said that this was a police paper, but the prisoners read it voraciously nonetheless. I had never read that particular weekly and opened it for the first time in my cell. The paper was then carrying a series of articles about the so-called ‘black wave’ and other ‘cultural deviations’, written in the language of an ideological executioner and issuing from the pen of Vuk Drašković . And on the very day on which I had been accused of false pretences, Revija 92 was delivered to the cell and by a stroke of good fortune contained the third text in the series, which described me as a ‘black-wave-ist’ and a writer who ‘continues to blacken the honour of Herzegovina and question the achievements of the NOB [National Liberation Struggle]’. In the centre of the page there was a row of photographs: first mine, then those of the filmmakers (likewise ‘black-wave-ists’) Žika Pavlović, Dušan Makavejev and Saša Petrović, as well as that of the historian Sima Ćirković, whose book the author charged with ‘fanning Serb nationalism’

The prisoners read this aloud and the paper was passed around so that everyone could see my picture (I have kept to this day the two-page spread from Revija 92). Following this they accepted me as one of their own, albeit engaged in a different profession. They no longer believed in my own story about adultery, rejecting this real event as a fantasy on my part. Revija 92 was for them an official party and police organ, so that when the paper attacked someone this was a sign that he was an enemy of the state, which by definition was both meritorious and dangerous. This is because every pickpocket, burglar, black-marketeer and cheat saw himself as an enemy of the state - and above all as a political offender. When they saw me described in the paper as a ‘black-wave-ist’, they nearly proclaimed me their ideologue. They all assured me that the fight had been a set-up, and maybe the woman too; that I didn’t know how the cops operated; and that I had in fact been arrested for political reasons, masquerading as a fight with ‘light physical injuries’. If I were prone to paranoia I might have fallen for this interpretation; but I knew that it was all a matter of coincidence, as often happens in life.

Since there was no free bed, I was sleeping on the floor; but the evening after Vuk’s text a prisoner gave me his bed, saying that it was an honour for him to do something for me, that in any case he was used to sleeping on the floor, and that moreover he had an air mattress. Luckily I stayed for only five more days in the Central Prison; but they were days when, thanks to the police journal Revija 92, I was able to swagger about among the prisoners and enjoy my brief moment of fame.

A schizophrenic or a Messiah?

I learned subsequently that the author of the series worked in the office of a political high-up, and that in his spare time he engaged in journalism and writing: he had published in literary journals prose works written in the most beautiful language of the Herzegovina area. I was also told that he was the author of several skilful paeans to Tito, and that he had become a party member while studying law. Bogdan Tirnanić insists that Vuk danced the Kozara ring dance together with Slobodan Milošević on 2 July 1968 in front of the law faculty. This was the well-trodden path of young people - especially Herzegovina paupers - who came to study in Belgrade with the backing of the [Partisan] Veterans’ Association. They enjoyed many privileges during their studies, such as grants and lodgings in student dormitories. They became party activists, were quickly promoted, and found it easy to get a job. They were not choosy about ways or means in pursuit of better positions, apartments or travel grants. Without moral scruples, they did everything they could to advance themselves and their careers. Consequently many of them spied on their colleagues and friends in return for small rewards.

It is said that in such a manner the little beast of this story became head of the Tanjug news agency’s Africa bureau, but was after a while withdrawn because he had begun to invent stories and report on events that had never happened, about wars in places where there were none and about peace where war was raging. Dr Ismet Cerić has told Radio B92 that Vuk, according to his colleague and psychiatrist Radovan Karadžić, was a schizophrenic, so it was not at all surprising that during his stay in Africa he saw things which did not happen and blanked out what did, since the ‘principal duality of his psychological apparatus’ led in practice to hallucinations or to the typical schizophrenic experience when the force of ‘true import’ is lost and the patient sinks increasingly into mystical experience and neurosis. I would not submit myself gladly to Karadžić’s methods, nor take for granted his interpretation of Vuk’s alleged schizophrenia; but a certain duality did become characteristic for both Serb leaders, the doctor and the patient - though the patient proved in better health than the doctor, who has entered into history as a mass murderer, indeed at the very top of the Balkan scale of war crimes.

Ideological testimonial

For a long while after the text in the police journal Revija 92 I heard nothing about Vuk Drašković, until at the start of the 1980s he suddenly cropped up with his novel Knife and became instantly famous. The promotions for his book became ever more stormy events, gathering large crowds - which was unusual for purely literary occasions. The police watched and attended these meetings, which acquired an increasingly political character, because it was not the novel itself that excited attention but the Ustasha crimes committed in World War II. The author himself kept adding fuel to the fires of political passion by appealing to emotions and low instincts; his malevolent tongue already then drew masses of people and the kind of readers who most probably had never read any other novel. Knife underwent several editions; Vuk tasted the joys of popularity and discovered a gift for oratory.

Curiosity led me to attend one of the promotions of Knife. So far as I can recall this took place at a sports hall in New Belgrade, with the crowd rivalling that of a well-attended basketball game. I think that at some point the police intervened. All I know is that I left before the mêlée, because the eruption of hatred and chauvinism had become unbearable. Vuk realized then that he could easily become a popular tribune, provided he played on national sentiment. He was delighted to be thrown out of the Party, because this would provide ideological testimony that he had parted company with a utopia and returned to his nation’s trough. He drank heavily from that trough in the following years, screeching with the voice of a national poet from many platforms, extolling in epic doggerel ‘the mystical spirit of my own tribe’, awakening it from the deep lethargy of so-called socialism and always blaming others for all his tribe’s frustrations - something that he did much of the time using frightening, even spooky, words and messages. For many years he howled like a hungry wolf on the squares of unhappy Serbian towns.

The literary manifestations of the 1990s were not the speciality of Vuk Drašković alone, but of most other Serb writers too. These were mainly marginal and unknown individuals, who had crawled out of their holes weapon in hand - the weapon of emotion - in order to set their tribe into motion, even though none of them knew where it was supposed to go. For they revelled in their own glory attained overnight and did not wish to lose it, even if it all led to the extremism that eventually occurred - the whole hullabaloo ending in a total defeat to which its creators, however, soon adapted. It was at this time that the outline of a new type of politician or political scoundrel started to emerge, who sought salvation in the nationalism that they had been fighting not long before - but that was the only place where one could be absolved of all Communist sins. The Communist became a vociferous anti-Communist, turning against everything he had stood for, spitting at the idols he had once adored. The former atheist became a militant believer. The former Communist now used all his arts of flattery to win over the mob. That is the species to which Vuk belongs. Born into a Partisan family, he became an ideological jobber before exchanging Tito for Draža [Mihailović] and reviving the Chetnik movement. He describes himself as a very devout man. Former Communists are fond of stressing their religious feelings, which the ideology to which they once belonged had denied to them; and it is precisely they who have increasingly imposed the Church and the clergy as new authorities, and subsequently - in line with their proclivity for rendering a thing untouchable - as new taboos.

Although I had long kept away from this bloodthirsty little beast, the events of the early 1990s linked me to him, and we found ourselves on several occasions sharing the same platform in our roles as opponents of the Milošević regime, although our political positions were always quite different. If I said anything on those occasions it was without enthusiasm, because I knew that crowds like militancy but rational discourse finds no echo among them, while politicians such as Vuk excelled in competing with one another as to who would be most effective in currying favour with the masses. Vuk did this better than the others: he delighted in his mission, and was also a skilled speaker; he moved well on this stage and manipulated every effect. Thus, for example, one day on Belgrade’s Republic Square a crane lifted him high into the sky, so that his words would flow down from above like those of God. What is more, he had the good fortune that thick snow was falling, so that the whole mise-en-scène acquired a mystical appearance, prompting the speaker to revert progressively to constructions copied from the Gospels, repeating in a Christ-like manner: ‘And verily I say unto you...’

Serb graves

Despite such effects, Vuk did not do well in the elections: getting just a few percentage points for all that yelling amounted to a fiasco. The Serb masses adored Slobo, while Vuk was something in the nature of a sideshow: they went to his meetings as if to a wedding or a revel. The mob was amused by his quips and his shouts, but few believed in what he was saying, except for the rare ones who took literally the claim that Serb borders are ‘wherever Serb graves are’ - all the way up to Vienna. But they usually got killed, dying to no purpose while fighting wars in foreign countries, blindly trusting in Vuk’s abstractions and ravings.

Thus Giška Božović, Vuk’s first bodyguard and commander of his Serb Guard, a former police informer who used to train young Chetniks for hard battle on the parade grounds below the Petrovaradin fortress and at Savača camp near the Borsko lake, fell at Gospić in Croatia. When his coffin arrived in Belgrade, Vuk spoke at the ‘hero’s’ grave, lamenting his chivalrous death. Vuk’s Serb Guard declined after Božović’s death and the murder of several of its commanders; but at its height it numbered some 40,000 Chetniks over the age of 18 who had passed through army training and special psychological tests.

Following the collapse of the Serb Guard, Vuk’s coat started to moult and his wild nature grew tamer. His war fantasies subsided, and he turned against those who were seriously putting into practice what he himself had propagated but was no longer able to practise. Bigger beasts had taken over, and war had come to Bosnia too, the worst in its bloody history, truly in the spirit of his belligerent earlier metaphor that he would cut off the hands of those Muslims who carried flags other than Serb ones. Vuk helped Milošević most when he thought he was working against him and resisting him, accusing him of having stolen his own ideas and programmes, because he believed that he alone was predestined for the role of supreme nationalist and warrior. But his opponent outdid him in everything. Moreover, he had behind him workers, peasants and the middle class, left and right, the intellectuals, the Serbian Academy of Arts and Science, the Writers’ Association, the Church, etc. Vuk retained a few disgruntled individuals, utterly disoriented people drawn from the Chetnik den, ‘super-heroes’ bedecked with all kinds of medals, and a small number of high-school students who fell for his Bohemian image and his sometimes wild and at other times neatly trimmed beard, which at the symbolic level made him look alternately manly, in mourning for Serbia’s decay, a follower of Christ, an artist, and lastly a Chetnik.

Translated from Feral Tribune (Split), 10 March 2006

|