|

My own Montenegro - and Serbia finally independent as well!

by Senad Pecanin

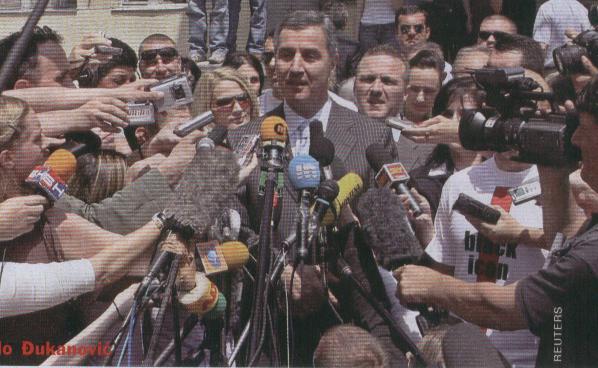

Milo Djukanovic announces victory

The penultimate act of the break-up of the former Yugoslavia was played out when Montenegro’s citizens by a narrow margin met the EU’s criteria for recognizing their state’s independence. The founding editor of Dani, himself born in Montenegro, describes the (post-)referendum mood refracted through the prism of his own and his family’s sensations.

My father is not one of those inclined to strong emotions or big words. We were all together in the family home that Sunday evening, for the first time in fifteen years, gathered around the television impatiently awaiting the announcement of the first preliminary results of the referendum vote.

‘By my father’s soul, if that ‘forest republic’ of yours [RS] would separate off and disappear, I wouldn’t mind dying tomorrow!’, my father says, fixing me with his gaze, as if prompting me to ask questions that would dispel my surprise at his big words. But I know him well and feel sure that he would use my query for the pleasure of offering an unexpected explanation of his position; so I fill my allotted role by merely raising my eyebrows. This, however, is enough for the retort: ‘What? Why are you surprised? I’m sixty-five, sixty-six, I’ve lived long enough and wouldn’t mind!’

Until a few years ago it never occurred to him that Montenegro would ever be in a position freely to decide upon its independence. I for my part did not believe that it would be the fifteen thousand or so voters like my father - those whom Montenegrin state terror had driven from their places and homes solely because they had ‘Turkish’ names - who would cross thousands of kilometres to participate in the referendum and with their votes secure the rebirth of a state whose backbone had been broken by the Great Serbia state policy at the Podgorica assembly back in 1918.

A historic event

Although Montenegro belongs to a region with an inflation of events too easily judged historic, 21 May 2006 is indeed that. For Montenegro’s independence means first of all Serbia’s independence. That it could be won without bloodshed, relying only on pen and song, seems as likely as that a majority of citizens of western Herzegovina would start feeling Bosnian rather than Croatian.

The supporters of the pro-independence bloc optimistically predicted that the result would surpass the 55% threshold demanded by the European Union. The more sober among them used optimism to hide their fear of the outcome.

The leaders of the Bloc for Union with Serbia, on the other hand, supported by the lieutenants of the Sandžak Party of Democratic Action Sulejman Ugljanin and Harun Hadžić, based their optimism on the Orthodox majority’s traditional feeling for a bond with Serbia. Their campaign was best described by Andrej Nikolaidis: ‘The face of the Montenegro of wrong assumptions, weird logic and sham motives became visible during the last days of the unionist campaign. A struggle against Montenegro’s independence under the cover of a struggle against Đukanović. At the closing unionist rally in Podgorica, calls against hatred and divisions; but hours after that the unionists rounded on Montenegrin flags, vandalized shops at the Budućnost stadium, and attacked the offices of the Movement for an Independent Montenegro. Predrag Bulatović declared in Tivat: ‘Our rallies are rallies of peace and tolerance, because Montenegro’s greatest asset is its multi-ethnic character.’ Showing full well that they had understood his message and had multi-ethnicity in their hearts, the public responded by singing: ‘King Peter’s Guard is on the march’, ‘General Draža’s sentinels are everywhere’, and ‘This is no Montenegro, but heroic Serb stock’.

In a country with the largest number of betting shops per capita, where only 10% of the adult population has a passport and 50% hardly ever uses it, attractive odds for prognosis of the referendum results. Like all other stupid consumers of the betting offer, instead of buying a ticket for a result between 53 and 57 percent of votes ‘for’ (1.9 euro for each invested euro), I bet on over 56% votes ‘for’ (2:1).

Less than an hour after the closing of the polling stations, it looked like I might indeed make money. The whole of Montenegro was in front of the TV screen, watching the programme led by the legendary sports commentator Milorad Đurković. His reporters, present at the offices of the two NGO’s - CESID and CEMI - that were monitoring the voting, came up with the information that, judging by the first preliminary results based on less than one third of polling stations, 56.3% of voters had voted for independence. There followed an eruption of enthusiasm from the pro-independence camp across the country. It took only a few minutes for the central town squares to be flooded with red Montenegrin banners. Viva, Viva Montenegro reverberated; there was firing from all manner of weapons including long-barrelled rifles; the sky grew iridescent with exploding multi-coloured rockets - luckily only those made for fireworks - for almost quarter of an hour.

Averting bloodshed

The following hours showed that the decision by CESID and CEMI to release that first estimate of the voting results was perhaps decisive for averting bloodshed across the country. The estimate of 56.3% of votes in favour of independence had cooled down the unionists and left most of them sitting dismayed in their homes and campaign offices. Their leader Predrag Bulatović addressed the public a few hours later, saying that the CESID-CEMI estimate of 56.3% was not accurate, and that according to the reports from polling stations available to the unionist bloc - the state union remained intact! He gained encouragement also from the fact that his declaration was followed by a new CESID-CEMI prognosis, based on new counts from a larger number of polling stations, according to which the independentists’ lead had practically disappeared - 55.3%, with a possible statistical error of plus/minus 0.4%! The mood among the supporters of independence promptly changed: the statistical error of 0.4% could mean that Montenegro remained in a ‘fraternal embrace’ with Serbia, despite 54.9% supporting independence. A frantic hunt began for Bensedin and Apaurin tablets. A friend asked my doctor friend: ‘Doctor, I took an Apaurin an hour and a half ago; can I take another one now, or should I wait a little longer?’ A man standing next to him smiled calmly, showing no sign of excitement; he told us he had been taking special tablets from abroad, the name of which he did not know so he called them orelo-gorelo.

The anxiety among the supporters of independence was additionally heightened by a constant postponement of the public appearance of representatives of the pro-sovereignty bloc. In Bijelo Polje, the celebrations were ended at midnight by the police ordering the music to be switched off in cafes whose forecourts were occupied by revellers. This was used as a pretext by the supporters of the pro-union bloc to gather in the centre and engage in petty provocations. Two of them demonstrated why Serb nationalism is not civilized: carrying an unfurled Serbian tricolour, they made a theatrical entrance among the pro-independence supporters. Removing all doubt as to whether a Serb nationalist when scratched turns into a Chetnik, one of them was wearing a traditional Serb military cap. The police nevertheless protected them, leaving them to parade in the town square while asking the previously peaceful revellers to fold up their Montenegrin banners. Perhaps lest they irritate the peaceful Chetniks. Finally the supporters of sovereignty too could relax, however: a representative of the Bloc for Independence told the public that there was no doubt that the number of voters supporting Montenegro’s independence was over the 55% threshold.

Following this, Milo Đukanović took a stroll round the most prestigious Podgorica cafes. A singer in front of one of them heralded him as ‘king and lord of Montenegro’ - a title that indeed fits him, given the concentration of power in his hands and his contribution to Montenegro’s independence.

Cetinje

On Monday evening, when the whole world apart from the Serb leaders in Podgorica and Belgrade had recognized the referendum results, a central victory celebration took place in Cetinje. It is impossible to overstate the contribution of this city to the renewal of Montenegro’s statehood. It was this city that during the 1990s preserved the honour of all Montenegro, which so much likes to stress its ‘humanity and courage’. This was the time when hordes of Montenegrin killers and looters were terrorizing Konavle, the Dubrovnik hinterland and Bosnia-Herzegovina. It was the time when the young Marko Popović, brother of the well-known Montenegrin poet Mija Popović, wrote verses - ‘From Lovćen’s summit the spirit cries, O Dubrovnik forgive us!’ - which became the unofficial anthem of all decent people there, who at their rallies, surrounded by hordes of Montenegrin reservists, would sing: ‘Sarajevo, my love’ as the city of the song was burning under Serb shells.

If only the late Boba Bogdanović, Montenegro’s bravest independence leader, and Antonije Abramović, first bishop of the renewed Montenegrin church, could have seen their Cetine on that Monday night! What divine injustice it is that the individual who did not hesitate beneath Lovćen, with a handful of supporters, to stand up to the mighty JNA, and the individual who was persecuted by both the Montenegrin government of the day and the mighty metropolitan Amfilohije of the mighty Serbian Orthodox Church, could not see the city awash with Montenegrin banners.

I have never been to a Rio de Janeiro carnival, but I imagine that its atmosphere must be just like the one I saw that evening in Cetinje. Thousands of supporters of independence from all over the country had streamed into the old capital city. Tall Montenegrin girls and tipsy Montenegrin men danced in the streets and traditional Montenegrin songs echoed from all sides. By contrast with Rio, Montenegro - as with all other Balkan peoples - resorts to oxen to mark historic moments: one of them was turning on a spit in the central town square, accompanied by hundreds of litres of donated Nikšić beer.

Exit from darkness? There is possibly no smaller nation with a greater number of war criminals and at the same time a greater number of decent and brave individuals as is the case for Montenegro. Even in Serbia during the aggression against Bosnia-Herzegovina, Bosniak refugees were not hunted down like those who believed in 1992 that, having fled their homes in Foča, Višegrad and Čajniče, they would find refuge from Karadžić’s executioners in Herceg-Novi. The Montenegrin police wrenched dozens of them from the arms of their tearful children and, after duly entering their professionally conducted action in the official records, handed them over to the ‘Republika Srpska authorities’, since when nothing has been heard of them.

I do not hold against my father his having travelled for three thousand kilometres in order to vote for Montenegro’s independence. An enormous number of Montenegrin citizens, including those who are still employed in the state and police apparatus, do not deserve to live in their free and independent state. But even if there were no other such places and individuals in Montenegro - and there are such - simply because of Cetinje and people like the late Dušan Gvozdenović, Dragoje Živković, Petko Pešukić, Rasko Hadžiahmetović, Miro Vicković and Vukić Pulević, or like Vojo Nikčević, Ivan Poček, Sreten Zeković, Radoslav Rotković, Sreten Perović, Stevo Vučinić, Pavle Jabučanin, Srećko Pavlović, Mladen Lompar, Jakov Mrvaljević, Sreten Vujović, Ljuba Perazić, Sreten Asanović, Miodrag Iličković, Jovan Nikolaidis, Milka Tadić, Rajko Cerović, Slobodan Rackovic, Milan Popović, Živko Andrijašević, Nebojša Redžić, Balša Brković, Željko Ivanović, Milika Pavlović, Žarko Rakčević, Ranko Krivokapić, Miroslav Radojčić, Nataša Novović and Branko Vojčić ... I do not hold it against my father. With independence, it is possible that he and thousands of others of his generation will be the last in Montenegro’s history who will be forced because of their ‘Turkish names’ and ‘historic guilt’ to flee their places and homes. It is possible too that future generations occupying the benches of my schools - ‘Risto Radović’ and ‘Marko Miljanov’ - will not feel my discomfort when listening to lectures on Gorski vijenac [Njegoš’s ‘Mountain Wreath’] and ‘the extermination of poturice’ [Christian converts to Islam]’. And it is possible that their teachers and professors will not call them to the blackboard as they did me with the words: ‘Come here, Turk!’.

I planned to send this text by e-mail from Bijelo Polje. But in the early hours of the afternoon in the semi-independent state the whole area north of Podgorica suffered a power cut. No one knew what had caused it. I returned home early that evening, leaving Montenegro’s north in darkness. I comfort myself that this has no symbolic meaning, and hope that it has nothing to do with the fact that it is precisely in this part of Montenegro that the majority of its citizens with the ‘wrong’ names live, those who brought it independence.

This report has been translated from Dani (Sarajevo), 20 May 2006

|