|

Cry the beloved former country

by David Rieff

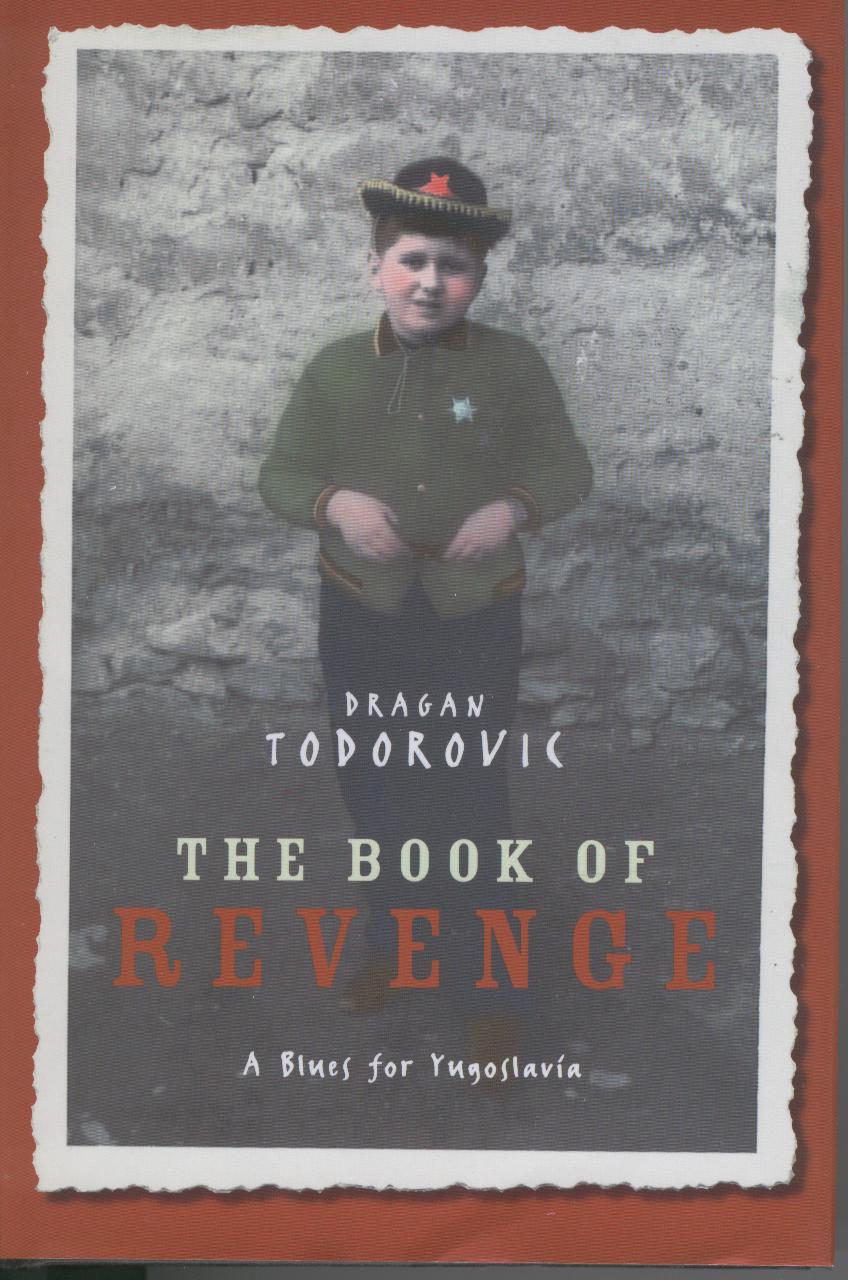

Review of The Book of Revenge: a blues for Yugoslavia by Dragan Todorović, Random House Canada, 386 pages, $34.95 Review of The Book of Revenge: a blues for Yugoslavia by Dragan Todorović, Random House Canada, 386 pages, $34.95

Reading Dragan Todorović's simultaneously affecting and infuriatingly self-pitying memoir, The Book of Revenge: a blues for Yugoslavia, is somewhat akin to entering a time warp, at least for those of us who covered the break-up of Yugoslavia in the first half of the 1990s (now, post-Iraq, it almost seems like ancient history).

In those days, what was often striking was the degree to which, as each war began - first in Slovenia, then in Croatia and finally in Bosnia-Herzegovina - the people affected would often confess that they had not paid much attention to the previous conflict. Once, during the siege of Sarajevo, a well-known Bosnian professor stopped himself in mid-sentence as he listed the horrors that had befallen his country and remarked to me, almost wonderingly, ‘You know, during the Croatian war, when the news of Vukovar would come on the evening news, I would often change the channel.’

Wounds breed self-absorption. That much at least is a commonplace. And there is nothing dishonourable about the fact, unless, of course, you want to say that it is dishonourable to be human. But what is human is not necessarily what is accurate. The version of the obsession with one's own fate to the exclusion of those of others that one frequently encountered in Serbia during the same period was to view the Yugoslav wars principally through the prism of Slobodan Milošević's rise, the subsequent extinction of Serb democracy and the collapse of the Yugoslavia that, to most if not all Serbs, had seemed like a relatively decent place to live, and its replacement by equally damnable nationalisms in all the former Yugoslav republics.

Yes, people in Belgrade and Niš were appalled by the siege of Sarajevo, but to ‘harp on it,’ as one exasperated Serb human-rights activist put it to me in the summer of 1994, was to miss the larger question: the fate of the decent, the ‘other,’ Serbia.

Born in the industrial city of Kragujevac in 1951, Dragan Todorović belongs to the generation of Yugoslavs not only too young to have endured the horrors of the Second World War but also the rigours of Titoism in its early, more ruthless incarnation. As generations go, in other words, his was a happy and, in an important sense, an innocent one. True, their elders regaled them not just with tales of the war but of the horrors of the Turkish ‘occupation,’ as Todorović rather revealingly describes it (the Turks ruled the Balkans for half a millennium; historically speaking, it was hardly an occupation in the sense, say, of the Germans in France between 1940 and 1944). But for Todorović growing up, life was marvellous. ‘Country life was fantastic,’ he writes at one point. And Marshal Tito ‘was our icon.’

Todorović's reverence for Tito while growing up, and the bereavement, incredulity and fear of the future that he and his family experienced at the old dictator's death, set the stage for the darker latter two-thirds of The Book of Revenge. In this, Todorović is following the well-worn path of most writers of his generation. ‘Yugoslavia,’ he writes, ‘was on its own.’ And for the remainder of the book, Todorović anatomizes the Cost of what followed both to himself, first as a journalist, then as an anti-Milošević pro-democracy activist, and finally as an exile in Canada, and to his country as it exploded and then disappeared.

The period in which Todorović worked for the cultural press in Belgrade, and began to find himself as a writer, is by far the strongest part of the book. Here, he plays to his strengths, above all a kind of sardonic resignation, mixed with an appealing refusal to take either himself or anyone else too seriously (perhaps Tito's death ended that phase of his life) and a fine eye for the ridiculous. Todorović is something of a specialist in the deadpan put-down, as when he writes of a student leader: ‘I recognized the type: probably a good student in high school, recommended early and made a member of the Communist Party, unlucky with girls, boring except to those interested in politics.’

And Todorović is decidedly not interested in politics. Actually, The Book of Revenge can be read as one young writer's personal cri de coeur at having to think about politics at all. The Renaissance historian Francesco Guicciardini once enjoined his readers not to mourn the fact that their city had declined, but rather the fact that they were unlucky enough to be born in the era when their city declined.

That is essentially Todorović's position, as well. Toward the end of the book, he writes of being in Belgrade in the 1980s, in ‘a year between wars.’ Without irony, he goes on to remark: ‘Everything was still good and Milošević not yet politically born.’ Somehow, I doubt it. Candid as it may be for him to describe his state of mind at the time, it is a mark of Todorović's lack of political acumen that he could actually believe such claptrap. Indeed, Todorović the child, mourning Tito's demise, was probably a more astute observer of Yugoslav realities.

Were Todorović only writing about himself, the politics of his book would not matter so much. But The Book of Revenge actually presents an intensely polemical account of the break-up of Yugoslavia along with the engaging memoir into which it is inserted.

And for all that Todorović emphasizes his detestation of Milošević and Serb nationalism, not to mention even more extreme figures such as Vojislav Š ešelj, his book is itself an exercise in the more moderate version of that same nationalism. It is the lament of the Belgrade liberal, circa 1994: ‘Milošević is a murderer, but so is Izetbegović in Sarajevo.’ And, of course, the effect of such moral equivalence - of saying, in effect, everyone is guilty - is actually to contend that no one is more guilty than anyone else.

Todorović may dress this up with irony. ‘Momir,’ he says to a friend in Belgrade at one point, ‘we're all centaurs, half men, half horses.’ But how can one credit, after the Srebrenica massacre - an event that, disgracefully, he never addresses with the requisite courage - the views of a writer who self-pityingly describes life in Belgrade in 1993 as ‘a humiliation,’ but does not see fit to acknowledge that life for people in besieged Sarajevo was rather worse.

It is not that Todorović doesn't care about Bosnia. To the contrary, he emphasizes that he idealized that republic as ‘a place where people of different nationalities, different religions and cultures, lived next door to one another,’ and recalls saying that if the war spread to Bosnia he ‘would run away from here.’ But at the same time, he repeats the standard Serb account of the beginnings of the Bosnian conflict -- an account with which, alas, the late Slobodan Milošević would have been quite comfortable.

That account places the onus on the Bosnian Muslims. According to Todorović's version, things start going wrong when ‘a Serb’ is killed in a drive-by shooting, and when ‘the Muslims massacred a military convoy pulling out of Sarajevo to ease the tension.’ It was then, he says, that ‘it all exploded.’

To put it charitably, this is claptrap: Only in a Serb nationalist history of the war would such distortions be possible. Indeed, anyone tempted to believe that the problem of Yugoslavia in the 1990s was Milošević and what Todorović calls his ‘brown-shirts’ need only read The Book of Revenge to see how deeply engrained the Serb sense of historical victimization and lack of responsibility for what happened in Bosnia was, precisely in decent people like Todorović and his friends.

There is one moment in his book when Todorović seems to verge on realizing the trap into which he has written himself. The passage is actually quite extraordinary. Todorović begins by asking himself when Serbs allowed the Milošević regime ‘to start changing us.’ He concludes, ‘Sarajevo was not the only city under siege: so were Belgrade and Kragujevac, and every town in Serbia. On the hills around Sarajevo were Serbs from Bosnia, hitting people with snipers and shells, turning them into memories; on the hills around our brains were Serbs from the media, hitting us with news and opinions, turning us into zombies.’

The obscenity and self-regard of the comparison take the breath away. And, for a moment, Todorović himself realizes this. ‘But wait,’ he writes, ‘even this thought came through the crack in my reason. I can't compare Sarajevo and Belgrade. I can't balance pains. I shouldn't contrast mental to actual death, or should I?’

No, he shouldn't. Yes, he does.

David Rieff's books include Slaughterhouse: Bosnia and the failure of the West and A Bed for the Night: humanitarianism in crisis. He lives in New York City. This review appeared in The Globe and Mail (Toronto), 25 March 2006

|