|

'Fra' Izet Imamovic - Gott ist eine!

by Faruk Šehic

The seven-hundred-year-old Catholic chapel in Srebrenica, totally destroyed in the war, has been renewed and handed over to the care of Izet Imamović. This is why the people of Srebrenica call him ‘Fra [Brother] Izet’. The seven-hundred-year-old Catholic chapel in Srebrenica, totally destroyed in the war, has been renewed and handed over to the care of Izet Imamović. This is why the people of Srebrenica call him ‘Fra [Brother] Izet’.

‘My neighbour Ramo was digging the foundations for his house and came across a grave. He came to my house and said: "I have found something; it might be gold." When we lifted the grave’s stone tablet we found bones. We rang up Vrhbosna and talked to Fra Marko Oršolić. I told him we had found something. He replied that it was the church of St Mary, because the Franciscans came to this area in 1290.’

This is what Izet Imamović, the guardian of the rebuilt Catholic chapel in Srebrenica, told us. Which is why the people here call him Fra Izet. We asked him if it was true that he was called Fra Izet. ‘I don’t know.’, he laughs, ‘I don’t know what fra means, maybe it is a title of sorts...’. He says that the Franciscans paid DM 600,000 for the clearing of the site and, Izet says, many frateri [friars] came on that occasion to Srebrenica.

‘Marko asked me back in 1991 if I would look after the chapel. It was all on TV. I left Srebrenica on 14 April 1992. I went to Tuzla, where I handed the keys to the Franciscans. When we returned we found the chapel destroyed. They kept farm animals in it. Then came the [Franciscan] Provincial and Oršolić and asked me again if I would look after it. They gave me the keys. We have 25 Catholic families here. The Catholics from Bratunac also come here for mass. Oršolić told me they had to pay me for my care. So they gave me DM 200 and food packets. Numerous TV crews from all over the world have been here. The foreigners ask me "How come that you, a Muslim, is looking after a Catholic chapel", and I tell them: "Gott is eine!".’

Izet explained to us how the Catholic chapel survived for centuries until the last war. ‘When the Turks came, most of the Catholics left, but a group of frateri remained in the monastery. After Sultan Mehmed Fatih had taken Srebrenica, he dined with the Franciscans. The sultan then said: ‘Let those who have left return, and let those who have remained practise their faith.’

Naser Orić as hero

On the day of our visit, the guardian of the catholic chapel Izet Imamović was celebrating his 78th birthday, so we went to the Mirsilija restaurant to talk to him about his unusual duty. Izet came back to Srebrenica in 2000 from Tuzla, where he had spent the whole war. ‘I had no children, and if I’d had any I would have lost them. My wife and I are on our own’, Izet tells us while celebrating his birthday with a glass of Tuzla Beer. He retired in 1984 after working as a driver for thirty-five years. ‘I drove everything under the sun.’ Now, as most people of Srebrenica do, he makes his living by letting rooms to foreigners. He is proud of his knowledge of the German language.

Izet says that the war was inevitable. ‘The Serbs and the Croats have always fought over Bosnia. You cannot imagine how they [the Serbs] killed everyone here who wasn’t a Serb - not just Muslims, but also Croats, Germans and Czechs!’ Izet talks while sipping the beer. He is very lively for his age. He gesticulates energetically while he talks. He appears serene even when talking about the most awful events: ‘I’ve had three by-pass operations. I’m well now. The operation was done by Dr Kabil. After the operation I asked the doctor if I could have two small brandies, and the doctor said I could, but not more than two. I stop drinking only at Ramadan. I’m not a practising Muslim, I’m an old SDP [former Communist party] supporter, and on the first day of Bajram I quickly have a shot.’

Every story in Bosnia naturally turns to the war. Izet tells us about Mladić standing next to his house saying: ‘Direction Bratunac! I give Srebrenica as a gift to the Serb people, as their revenge for the dahije!’ ‘The truth is that Serbs were never a majority in this town. They burnt down 24 mosques, while their church remained untouched throughout the war, because Islam does not allow the destruction of other churches.’, says Izet. ‘There are more Muslims than Serbs today in the [Srebrenica] municipality. The Serbs are now very humble, because the šehid [‘martyr’, war victim] families receive a fair amount of money, and when they need to have their logs cut the Serbs do it for them. Before the war there were 74.6% Muslims, 24% Serbs and the rest were Catholics.’ Izet tells us that Naser [Orić]’s release did not please the Serbs, who said that the Muslims were plotting with the international community and that the Serbs were not a genocidal people. ‘Naser is a hero for us, and a criminal for them.’, explains Izet Imamović.

Izet’s sabur [forbearance]

When Izet returned to Srebrenica after the war, his first neighbour was a Serb from the Krajina [northwestern Bosnia]. He came to ask for flour, since he had nothing to eat. ‘I gave him flour, oil, potatoes... The neighbour told me: "We were told to come here, that the Turks would never return." I replied: "The Turks, of course, will never return, but those whose houses are here are bound to do so".’ He [Izet] told us about one time when they sang ‘Knife, wire, Srebrenica’ near the ‘Alma Ras’ factory, but says that none of them ever threw as much as a stone into his front yard. ‘Only one of them came seeking to offend me. He said: "Have you washed your hands today? Take my dick out, so I can take a piss.’ I told him he should be ashamed of himself, for I could be his father.

A miner told Izet he did not know him. Nevertheless he [Izet] greeted him every day, even though the miner would turn his head away. ‘I still carried on greeting him, and in the end he responded.’

Nine years ago, when his wife came to Srebrenica for the first time, a certain café owner called Rakić assaulted her. He said he would rape her in public. ‘A court clerk called Jela went for the mayor, but Rankić ran off, only to come back with a war invalid who struck the table with his fist and said: "What does the balinkura [Muslim bitch] want?" My wife was saved by an American patrol who took her to the police station. There they asked her to identify the man. As she walked through the town all the windows were open - everyone had heard that a Muslim woman had returned to Srebrenica. The police took her to Bratunac and thus saved her, but no proceedings were ever instituted. Thank God, things have quietened down since then and we have no problems any longer.’

Izet noticed I was smoking a lot, and asked me whether I could live on twenty cigarettes a day. ‘I used to smoke sixty a day, and then one morning I woke up coughing. Then I went to the bridge over the Drina and stopped smoking.’ We asked Izet if he would have another beer. ‘No, I couldn’t; it would spoil my appetite. I have roast kid for dinner.’

Byword for horror

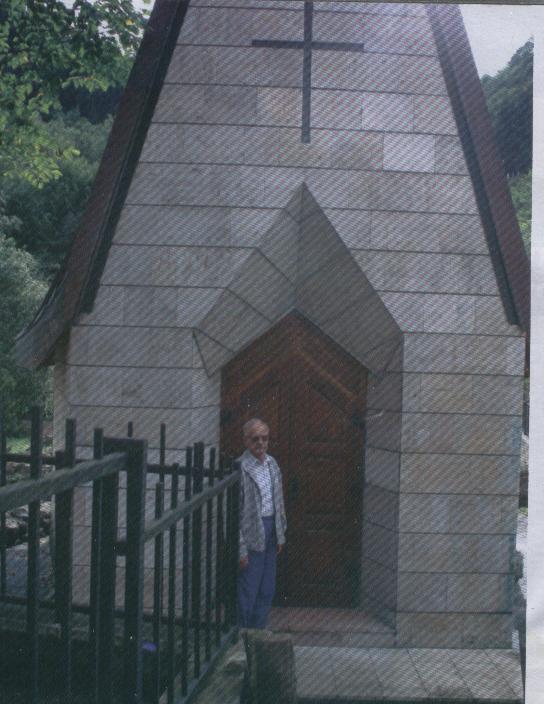

Srebrenica is a town that extends along a long road meandering between high green hills with houses surging up them like climbing plants. The falling rain strengthened the depressing feeling emanating from the place. We came to Izet’s house in order to photograph the Catholic chapel situated in a yard squeezed between two houses. The chapel appeared out of this world. The inscription above the massive wooden doors reads: ‘Built by the Franciscans of Silver Bosnia on the seventh centenary of the arrival of the Franciscans in Bosnia, 1291-1991.’ Next to the chapel one can see the foundations of the old church, together with several crypts. One of them displays a shield with the hilt of a sword protruding from it. There is a standing monument with floral decoration. Izet broke the charmed silence: ‘I’m the only one in the neighbourhood who didn’t lose a family member.’

Next we climb to the plateau above the Hunter’s House. From there you see the town as if in the palm of your hand: the white mosque, the Orthodox church, and as I look at the spot where I am standing I have the feeling that I was here once before, or that in some misty past I had dreamt that very scene. There is a huge cross on the Turkish fortress, made of welded pipes. Izet tells me the Orthodox clergy put it up there, saying it had once been their church - that our side had cut down the cross and the Serbs had now put it back. On the path from the Turkish fortress stands the Jerinja fort. which according to Izet once belonged to an Austrian empress whom they called Jerinja the Cursed. Srebrenica is a town in which one finds oneself literally suffocating, as though the air lacked oxygen.

When we set off to Srebrenica to do a story on Izet, I had imagined it would be a diverting human story, but was forced to admit in the end that no story about Srebrenica could be diverting, not even eleven years after the genocide.

Translated from Start (Sarajevo), 5 September 2006

|