|

Child of The Service

by Filip Švarm

Wednesday, 12 March 2003, dawned as a sunny, spring-like day. At Kula, in the ‘Radoslav Kostić’ Centre of the Serbian government’s Units for Special Operations (JOS), the situation was normal: reveille, gymnastics, training in line with the plan and programme. Few in fact knew what these people’s job was. The media flattered them, the politicians respected them. The army and the policy bowed before them, while all of Serbia feared them. There were also called Red Berets or, simply and brutally, the Unit.

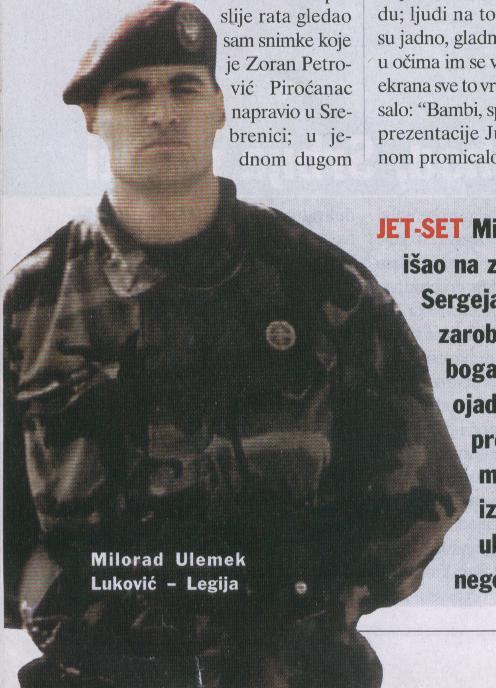

The news that at 12.25 in the afternoon prime minister Zoran Đinđić had been shot by a sniper reached Kula twenty minutes later. Members of the Red Berets started to arrive from all over: from the Command on Senjak, the diving-diversionary team from the river Sava, members of the Section for the Protection of Persons and Objects, the logisticians from the Lipovica base, the frontline fighting unit in Vranja... That same evening the Unit experienced a collective shock when the government announced that Milorad Ulemek Legija and the Zemun Clan, the most powerful mafia group in the region, were responsible for Đinđić’s murder. Although he was then only thirty-five, Legija was already a retired police colonel. For the Unit, however, he was their first, true and only commander. Although Serbia was placed under a state of emergency, the Red Berets waited for days to be allocated a task. They never got it. Charged with committing a whole number of serious crimes, most of its commanders were arrested. The formation was quietly dissolved three days later.

How did it come about that the man whom Đinđić had described as a hero of 5 October [2000: Milošević’s overthrow] came to be charged as the main organiser of his murder? How was it possible that the deputy commander of JOS, sub-colonel Zvezdan Jovanović, came to be charged with pulling the trigger? How did it happen that the most serious political crimes - murder, kidnapping, assassinations - were committed by the Unit’s members? In order to answer at least some of these questions, it is necessary to go to the very beginning of the story.

The Roots

It all began on the night of 3 and 4 April 1991, when a group of armed men set off from Belgrade in the direction of Knin. Of these five, two were important: Franko Simonović Frenki and Dragan Vasiljković, subsequently known as Captain Dragan. What happened was that twenty days earlier - on 9 March 1991 - demonstrations organised by the opposition had seriously shaken Milošević’s authoritarian regime. The Serbian president now decided to exploit the position of the Serbs in Croatia in order to divide the opposition. In a speech on 16 March 1991, delivered at a closed meeting of heads of Serbian municipalities, Milošević promised to form a unit to help the Krajina Serbs. He said: ‘The government has been given the task of forming suitable units that would ensure our security in any event, i.e. allow us to defend the interests of our republic and, by God, also the interests of the Serb people outside Serbia.’

The execution of the order to create the Unit was entrusted to one of Milošević’s most trusted and capable henchmen: the head of the Serbian state security service, Jovica Stanišić. Stanišić delegated the task of forming the Unit on the ground to the operative and adventurer Franko Simatović Frenki. Since Yugoslavia was still in existence, the Unit was not to be formally linked to Belgrade, so that Frenki could not count on the help of the Serbian police. Enjoying, however, full logistical support from the state security service, he was able to find and recruit suitable men.

Captain Dragan was the very type that Frenki was looking for: completely unknown, with military training and an adventurer by nature. Frenki must have known too that Captain Dragan had visited Knin in October 1990, and that his offer to train the Krajina police had found no response. Was it still on? At the end of March 1991 Frenki met Captain Dragan at the Belgrade hotel Metropol. ‘I believe I must have made a strong impression on them during our conversation’, Captain Dragan says. ‘I formed a kind of friendship with Frenki: it went further than the official talk.’ As soon as they arrived in Knin, Frenki and Captain Dragan called on the Krajina minister of the interior, Milan Martić, who took them to the Krajina police base in the village of Golubić. There, on 5 April 1991, Captain Dragan took command.

‘They looked nothing like’, says Captain Dragan. ‘They wore all kinds of uniforms with all sorts of insignia - from Serbian royal badges to five-pointed stars. People wore what they wanted. It was my impression that the strongest among them also enjoyed the greatest authority. I managed to sort them out very quickly. Within a week there was a drastic change. I managed to arrest a few of the most vocal and strongest leaders, get rid of them at this stage of the story, or put them in their place. I soon introduced order in that police unit.’

None of the few hundred lawless Krajina policemen whom this self-assured man without a surname was lining up into ranks could have known that they were witnessing the birth of the Unit. It would continue to act, largely in secret, for the next twelve years under various names, some official and some not. Depending on the period, some called them Frenkijevci, others the Unit for Anti-terrorist Action, others still the Unit for Special Operations - but above all the Red Berets. The Unit would subsequently undergo many changes, but its essential nature - an undercover armed formation of the state security service - remained the same. The JSO’s spokesman described it ten years later, at the time of the Unit’s armed rebellion, as follows: ‘The Unit is the child of the [state security] service. It was formed at difficult times for the Serb land and its people; and it always fought in full compliance with the Geneva convention. This is why we are proud of the [state security] service within the framework of which we wish to remain, because it is our Unit’s very heart.’

The Other Branch

In the spring of 1991 armed incidents, in which the JNA increasingly involved itself, multiplied also in eastern Slavonia. In this part of Croatia bordering on Serbia, the state security service faced a difficult task: the Serbs here enjoyed neither the position as a dominant majority nor the political infrastructure of those in the Krajina. The SDS here depended far more on Belgrade, and stood in far greater need of the Unit.

What this involved became clear on the night of 1 - 2 May 1991, when, in addition to a local Serb man, twelve Croatian policemen died and dozens were wounded during a big clash in Borovo Selo. Was the local police capable of, and organised for, this action? Six years later, during the celebration of the Unit’s Day, Franki made a speech in which he let it be known that a more serious and better trained force had been in action there: ‘It [the Unit] was formed on 4 May 1991, at the time of Yugoslavia’s break-up, and was from the start directly involved in protecting national security in a situation when the existence of the Serb people was under threat throughout its ethnic area’, he told the assembled at Kula. Why was 4 April chosen as the Unit’s Day rather than some event in the Knin area? Is it because state security men, who came to form the core of the Unit, had taken part two days earlier in the clash at Borovo Selo? Or was it because Stanišić had formally signed the order for its formation on that day?

Eastern Slavonia, close to Serbia and far more wealthy than the rest of Krajina, was an irresistible bait for self-proclaimed vojvode [warlords]and weekend warriors. As soon as he was installed as commander of the local Serb Territorial Defence, Radovan Stojičić Badža, who was then commander of the Special Anti-Terrorist Unit (SAJ) of the Serbian police, quickly formed his branch of the Unit which he presented as one of the many volunteer formations.

What more is there to say about the best-known Serb paramilitary commander, Željko Ražnatović Arkan? Though many believe that Arkan and his Serb Volunteer Guard was in the main an autochthonous phenomenon, the Guard was in fact Badža’s part of the Unit, formed by the state security service in the same way as was Frenki’s branch in Knin. In line with Arkan’s nature, a good part of the Guard’s commanding cadre consisted of his partners from the criminal underworld, with fat police dossiers. Captain Dragan, who helped to train them, says: ‘I recall being taken through the sleeping quarters by Arkan, who said to me in one of the rooms: "This room contains two hundred and fifty years in prison."’ What more is there to say about the best-known Serb paramilitary commander, Željko Ražnatović Arkan? Though many believe that Arkan and his Serb Volunteer Guard was in the main an autochthonous phenomenon, the Guard was in fact Badža’s part of the Unit, formed by the state security service in the same way as was Frenki’s branch in Knin. In line with Arkan’s nature, a good part of the Guard’s commanding cadre consisted of his partners from the criminal underworld, with fat police dossiers. Captain Dragan, who helped to train them, says: ‘I recall being taken through the sleeping quarters by Arkan, who said to me in one of the rooms: "This room contains two hundred and fifty years in prison."’

It is clear that a formation of this nature could be controlled only with a strong arm. According to Borislav Pelević, former general in Arkan’s army ‘We had a punishment for them which was taken from the Serbian military tradition: twenty-five strokes on the buttocks at the flag pole in front of the whole Guard. The baton used did not hurt too badly.’ A former officer in Arkan’s Guard, Žuti, explains: ‘We used a truncheon called an "Ustasha-thumper", it was a thick electrical cable. When that hits you, brother, it drives your liver or stomach up to your brain.’ Captain Dragan says: ‘The volunteers were really scared of Arkan; he used fear to maintain discipline.’

The Red Berets

In this period the Knin Unit, after undergoing a baptism of fire in June 1991 at the Ljubovo pass near Gospić, was used in the battles in Lika, Banija and Kordun. One day, during one of the cyclical conflicts between the Krajina president Milan Babić and Milan Martić over control of the Krajina army and police, Captain Dragan took Martić’s side. Babić kept complaining to Milošević until Frenki called up Captain Dragan. ‘He told me that the chief wished to see me in Belgrade. Jovica [Stanišić] , in fact, visited me and told me bluntly that I was banned from Krajina. I asked why. He told me that from my position I was unable to see things which were visible from a higher position. He then told me that if I refused to obey him, he would have to shut me out. He told me in so many words: ‘Captain, you must understand that I have no other choice but to shut you out. You are not allowed to go back to Krajina again.’ In this period the Knin Unit, after undergoing a baptism of fire in June 1991 at the Ljubovo pass near Gospić, was used in the battles in Lika, Banija and Kordun. One day, during one of the cyclical conflicts between the Krajina president Milan Babić and Milan Martić over control of the Krajina army and police, Captain Dragan took Martić’s side. Babić kept complaining to Milošević until Frenki called up Captain Dragan. ‘He told me that the chief wished to see me in Belgrade. Jovica [Stanišić] , in fact, visited me and told me bluntly that I was banned from Krajina. I asked why. He told me that from my position I was unable to see things which were visible from a higher position. He then told me that if I refused to obey him, he would have to shut me out. He told me in so many words: ‘Captain, you must understand that I have no other choice but to shut you out. You are not allowed to go back to Krajina again.’

Stanišić and Frenki decided in fact that the Knin Unit had succumbed to the influence of local politicians, as a result of which the Knindje - as the press called them - were disbanded. But Frenki kept a select group with him. Their new task, far more important than training police or fighting, was to establish firm control over the Knin government. Six years later Milošević congratulated this strictly undercover group on the Unit Day celebration in Kula.

All of them, and the Unit itself, were henceforth to be marked by one of Captain Dragan’s last moves before leaving the Krajina at the beginning of July 1991. ‘Red berets were introduced after the battle for Glina’, says Captain Dragan. ‘Twenty-one men took part in it. I had nothing else to give them. I had no medals and no money.’ From that time on and until the Unit’s dissolution, the red beret was its trade-mark and name. During the wars in Croatia, Bosnia and Kosovo, few people knew about Frenki and Legija, about their men or their actual business, but there was hardly anyone who had not heard of the Red Berets. Those two words meant licence to kill. The Unit changed names, tasks and commanders, but kept wearing the red beret. Captain Dragan explains: ‘The Unit always existed, whether formally or informally, whether it numbered thirteen or, in the end, three hundred men. At some point I had the command, then Frenki and then Legija. But the Unit remained.’

When, because of Vukovar, the war’s centre of gravity moved to eastern Slavonia, Arkan did not have financial or political problems of the kind that had beset Captain Dragan. From his base at Erdut, in which it spent - with one break - five years, his Guard waged military campaigns in Croatia and later also in Bosnia. This part of the Unit never numbered more than three hundred men, and rarely undertook independent action. It was accompanied everywhere by pillage and war crimes. Badža’s idea in 1991 was that they would supply a shock force for the JNA. Although the JNA generals were loyal to Milošević, at the end of 1991 he got rid of the JNA high command for the simple reason that he had not appointed them. In the campaign designed to prepare the public for this, the media accused the army of incompetence and treason and cited Arkan and his part of the Unit as an example of military courage and patriotism.

Some generals got the message. Among the first to do so was the commander of the Novi Sad corps, Andrija Biorčević. Speaking together with Arkan at a celebration, General Biorčević said: ‘Mr Arkan is for me an honest and decent Serb. He was a rich man even before this war. He lost more from this war than he got out of it. Where is your wound? Show it, Serb hero! Look at his finger! Which one? See what he’s like. I tell him to go and cure himself, and he says to me: "I am with you!"’

At the start of 1992, following the signing of a cease-fire, the JNA withdrew from Croatia. Badža, who was appointed head of the Serbian uniformed police, also returned to Belgrade. But the Unit remained in Slavonia. With permission from Stanišić and Badža, Arkan established a monopoly on all transactions in eastern Slavonia, using his firms as cover. He smuggled petrol and cigarettes to and from Serbia, sold wine looted from the cellars of Erdut, felled and exported oak timber. Members of the Guard employed in this enterprise were called Engineers. Arkan, of course, was not the only one who did such things. It is on the basis of this kind of business, always with an obligatory tax paid to the state security service, that Milošević’s new-rich elite emerged.

Although at the start of 1992 the Unit from Knin looked like a poor relation in comparison with Arkan’s Guard, its importance for the state security was far greater. ‘Frenki collected around him a group of no more than fifteen men’, says Captain Dragan. ‘He took them to Fruška Gora [in Vojvodina] where he established a camp.’ Motel Ležimir on Fruška Gora, which today is a deserted and neglected site, was a strategic choice: in less than an hour the Red Berets could reach eastern Slavonia, where the war had just ended, and Bosnia, where it was about to start. Although the commanding cadre was composed mainly of veterans from Krajina,. Ležimir was not the same as Golubići. The Unit was now enlarged with recruits from Serbia, and re-fashioned using Arkan’s methods. Captain Dragan was no longer needed there either. According to Dragan: ‘Žika Montenegrin was appointed as the Unit’s commander. He is in many ways an excellent man, a hero when he commanded a unit of five men, but his appointment as commander of the Unit was a great error for both him and the Unit.’

At Ležimir the Red Berets acquired the insignia which they would wear until the end. ‘They were, in fact, the forerunners of JSO. It was Frenki’s idea to form JSO. He lobbied a long time to be allowed to do that’, says Captain Dragan. Stanišić refused, for political reasons, to fulfil Frenki’s desire for the Red Berets to become a regular unit of the Serbian police. The Unit continued to exist without being officially registered.

Dangerous Men

As soon as the war ended in Croatia, in the spring of 1992 it flared up in Bosnia. It was the most serious war in Europe since 1945, accompanied by terrible destruction, war crimes and ethnic cleansing. Arkan’s Guard immediately joined the action to seize eastern Bosnia. According to General Manojlo Milanović, chief of staff of the RS army: ‘Arkan was a special problem. By the time I reached the war front, on 11 May 1992, Arkan had already finished the job in Bijeljina and Zvornik. What was typical for the Serb Volunteer Guard was that, on its return from RS and RSK, its columns included in addition to tanks and transporters also a large number of articulated lorries. That meant looting.’

It was at this time that Milorad Ulemek Legija, ex-robber of a sports-equipment shop in New Belgrade, joined Arkan’s Guard. Igor Gajić, a former soldier of the RS army, recounts: ‘At this time there were six or seven Legijas. Whoever had spent time in France, not necessarily in the Legion, was called Legija.’ Ten years later, when Legija as commander of the Unit held the government elected in October 2000 under siege, Serbia would pronounce his nickname with fear. ‘Legija was militarily the most educated of all those who were with Arkan’, says Dragan Vasiljković. ‘He was young, energetic, decisive.’ Borislav Pelević: ‘It soon became clear that Legija was very knowledgeable, which is why he became a chief instructor before being appointed one of the main commanders in the Guard.’ According to a former member of the Unit, ‘Joca’, Legija gave the impression of being ‘a man without scruples, who could do a big job and was not scared of the task or the bullet.’ It was at this time that Milorad Ulemek Legija, ex-robber of a sports-equipment shop in New Belgrade, joined Arkan’s Guard. Igor Gajić, a former soldier of the RS army, recounts: ‘At this time there were six or seven Legijas. Whoever had spent time in France, not necessarily in the Legion, was called Legija.’ Ten years later, when Legija as commander of the Unit held the government elected in October 2000 under siege, Serbia would pronounce his nickname with fear. ‘Legija was militarily the most educated of all those who were with Arkan’, says Dragan Vasiljković. ‘He was young, energetic, decisive.’ Borislav Pelević: ‘It soon became clear that Legija was very knowledgeable, which is why he became a chief instructor before being appointed one of the main commanders in the Guard.’ According to a former member of the Unit, ‘Joca’, Legija gave the impression of being ‘a man without scruples, who could do a big job and was not scared of the task or the bullet.’

The Unit from Ležimir, known as the Red Berets, was divided into two fighting groups and sent at the start of April 1992 to fight in Bosnia. ‘We were issued instructions and taken by helicopter to Han Pijesak.’, recalls Joca. ‘We landed next to General Ratko Mladić’s headquarters. We were transported from there to Sarajevo, and installed in the middle-level police school on Vraca. There we were given certain instructions by our host Karl Kariška, commander of a special unit.’ During the first months of the war, before the RS army and police were fully organised, the Red Berets acted as a shock group at strategic points between Sarajevo and Herzegovina. ‘The Unit was at first organised into operational groups, or as we called them fighting groups’, explains Joca. ‘The operational group to which I belonged had forty-two men. They were people from all parts, except from Montenegro. The Montenegrins had their own operational group and did not mix much with others, though they behaved correctly. According to some indications, the Unit had two thousand men.’

The RS army commander Ratko Mladić was among the first who changed from being a JNA general into a Serb general. He began his wartime career as commander of the Knin corps in 1991. Cruel and ruthless, but also charismatic, he did not tolerate armed formations that were outside his personal control. As soon as his main staff began to function, Arkan had to end his campaign in Bosnia. But in the case of the Red Berets under Frenki’s command, the stubborn Mladić was forced to retreat. ‘Badža was in uniform, and Stanišić in civilian dress.’, says General Milovanović. ‘I asked General Života Panić who these people were. He told me that Stanišić was from the state security service - that’s all. I was astonished at how well Stanišić knew our situation in the Drina valley. He knew some things better than me. He knew who was fighting in which village, who was in command, etc. He rather impressed me.’ The Unit fought in Bosnia until the end of the war. From the very start one of its most important activities was to organise and train the local special army and police sections, such as the Panthers in Bijelinja commanded by Ljubiša Savić ‘Mauzer’. ‘As far as my fighting group is concerned, after Sarajevo we went to Ozren, then supported Mauzer’s Panthers, after which came Grahovo, Prijedor, the forests north of Sanski Most’, recounts Joca. Only Frenki, however, had the full list of the places in which the Unit acted: ‘In RSK: Golubići, Dinara, Obrovac, Gračac, Plitvice, Š amarica, Petrova Gora, Lički Osik, Benimir, Ilok, Vukovar. In RS: Banja Luka, Doboj, Š amac, Brčko, Bijeljina, Trebinje, Višegrad, Ozren, Mrkonjic Grad....’

‘They were a motley crew’, recalls Željko Kopanja, proprietor of the Banja Luka daily Nezavisne novine. ‘We did not know who was a "red beret" and who a member of the RS special police unit, since they were one and the same thing. When Arkan’s men came, they too were included in the RS special police units.’ Joca explains why: ‘You should know that many units emerged from the Red Berets. For example, the Wolves from Vučijak. Those people were trained with us, and when they returned to their places they formed their own units on the basis of what they had learnt from us.’ In contrast to Arkan’s Guard, the Red Berets worked in silence. Few people knew the name of their fighting- group commanders. Every now and then a name would come up. ‘Rajo Božović? I heard his name in the context of "dangerous men",’ says Kopanja. (To be continued.)

Translated from Vreme (Belgrade), 7 September 2006

|